“If you can’t beat them, join them.”

This was the phrase my head of department responded with when I first told him I wanted to use Minecraft Education in my science lessons.

Fast forward three years and Minecraft supports some of my easiest and most enjoyable lessons, resulting in deeper discussions as I explore with students why they decided to model a concept in a certain way. I also use it to spot misconceptions and see if students can use scientific terminology appropriately.

Minecraft is a popular computer game among school children. Everything in it is made from different kinds of blocks. Think of it as virtual Lego, where students can most probably build anything as long as they can imagine it.

Minecraft Education is a paid upgrade of the game designed for schools and offering extra tailored blocks (e.g. chemistry blocks) and tools that allow students to output their work as a pdf file (see further information).

However, there is no reason why regular Minecraft cannot be used, for example I find myself increasingly collecting video responses from students who have recorded YouTube-style explainers.

Getting started

I introduced Minecraft at my school by trialling it with a year 9 class. A paid subscription was purchased, and it was explained that as part of a trial they would need to use it appropriately. We set out to use it once per-topic over the year.

The first time I used it I designed a task that academically speaking was almost impossible to fail. The students had to design particle diagrams of solids, liquids, and gases followed by before, middle, and end images of particles during diffusion and dissolving. The key outcome was for them to learn how to output the work in a format that I could mark.

As the year went on my tasks got bigger and more ambitious as we learnt how to use Minecraft together. Soon, the students were also coming up with creative and appropriate ways to use the game. The feedback from year 9 students after the trial was positive, with the vast majority agreeing that Minecraft had supported their learning.

During the trial, a couple of other subject teachers tried it out too. This included biology, where students illustrated plant growth variables by designing the perfect greenhouse (pictured above), and religious studies, where they explored free will by recreating famous film scenes.

I now use Minecraft across my key stage 3, 4, and 5 science teaching. In year 8 my favourite is a model walkthrough of the digestive system, with organ functions explained throughout. Students have also enjoyed exploring natural selection and extinction in a mini end-of-year research project.

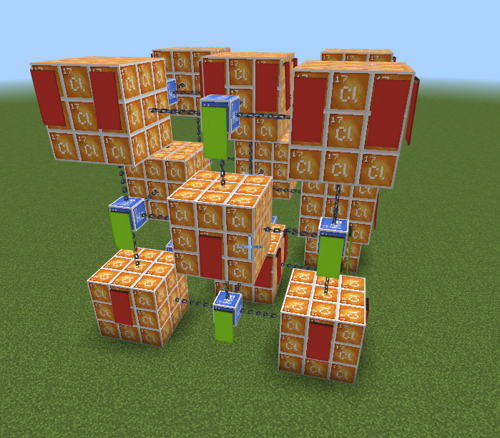

At key stage 4, we have modelled bonding in chemistry allowing students to discuss the differences between ionic and covalent bonding and the difference between giant and molecular structures. We also build organic molecules.

At A level I have had some impressive video walkthroughs of creations covering molecular shapes, cell membranes, and eukaryotic cells, allowing students to talk and walk through 3D structures of atomic-level features that can be difficult to visualise.

Bonding: An example of Minecraft being used to illustrate bonding in key stage 4 chemistry

I can envisage the platform being used across other subjects. Despite most of my examples being science-based my religious studies colleague continues to use it, producing some impressive videos of temples, built collaboratively, where students walk through their hand-made structures explaining the symbolism and imagery used.

In history, I can see it being used to recreate historical sites, such as the trenches. Indeed, we now have a popular Minecraft History Club run at lunchtime where students have built accurate representations of Medieval castles and villages.

Elsewhere, exploring geographical landscapes such as glaciers in geography could work well, while communicating character development in English by recreating several scenes in a text is an idea inspired by one year 8 group which incorporated Animal Farm themes and settings into a natural selection video.

Some top tips

- Training: I recommend the online training for those who know very little about Minecraft. See further information below for a link to some Microsoft Learn Teacher Academy training.

- Settings: Tell students to use creative mode, turn off weather and day cycles, and use a flat world.

- Start small: Make the first task about knowledge consolidation and communication.

- Marking: Provide 5 or 10 marks for work focusing on the subject content.

- Flexibility: Have an alternative task for those who really do not want to use it.

Final thoughts

Using Minecraft in the classroom is an example of game-based learning where the teacher takes an existing game to meet specific learning objectives. This is not to be confused with gamification, where the teacher incorporates game features into their lessons such as competitions, leaderboards, and prizes.

It is also an example of virtual reality (VR) where work is created in a virtual world. VR can offer advantages to teaching when the teacher wishes to explore micro to macro-level concepts that are difficult to visit or scale visually, such as atoms, geographical landscapes, and planets.

I have found that Minecraft can offer some of the most rewarding and creative lessons and mention my marking is certainly more varied and interesting now! Good examples are always shared with the class to inspire and demonstrate creativity for future tasks.

Most students get very engaged with tasks, which leads to much deeper discussions on ideas and concepts. It is also a way to engage with the learning and understanding of quieter students who rarely speak up in lessons.

- Dr Ben Scott is a secondary school science teacher, specialising in biology and chemistry and has eight years of teaching experience. He is also a digital research and development coordinator as part of the teaching and learning team at his school.

Further information & resources

- Minecraft Education: Chemistry lab journal: https://education.minecraft.net/wp-content/uploads/ChemistryLab_Journal.pdf

- Microsoft Learn: Minecraft Education: Teacher Academy training: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/training/paths/minecraft-teacher-academy/