One of the biggest changes made to the accountability system in recent years was the introduction of Progress 8 in 2015/16 as the principle headline performance measure for all secondary schools in England (secondary schools were given the opportunity to opt into the new accountability measures in 2014/15, although only about 10 per cent did).

This marked an important shift by Department for Education (DfE) ministers away from using a threshold measure as the main way of judging secondary school performance to using a value-added measure.

This was an important development because, as readers of this article will know, prior attainment is a key factor in explaining how well children do at the end of school.

Indeed, Education Endowment Foundation analysis (2013) shows that a pre-test score (key stage 2) explains around half of the variation in GCSE scores (depending on the subject).

Prior to the introduction of Progress 8, the headline threshold measure in use was the proportion of pupils in a school achieving five or more A* to C grade passes, including English and maths.

There had been several concerns about using a threshold measure to hold schools to account. As well as not taking account of pupils’ prior attainment, there were fears that some schools were focusing disproportionate effort and resource on pupils on the C/D grade borderline.

NFER’s own research (2018) into accountability systems in different countries highlights the way in which threshold measures can distort school behaviour, encouraging them to focus on children just below the threshold, at the expense of those expected to perform comfortably above or well below the threshold.

Progress 8 was designed to address these concerns. The DfE also said it would encourage schools to offer a broad and balanced curriculum, with a focus on an academic core at key stage 4, to focus on all of their pupils – as every increase in a grade will count towards their score – and to measure performance across a broader curriculum of eight qualifications.

Should Progress 8 also take account of other factors?

Many commentators agree that Progress 8 has been an improvement compared to the previous threshold measure as it takes account of, or “controls” for, prior attainment.

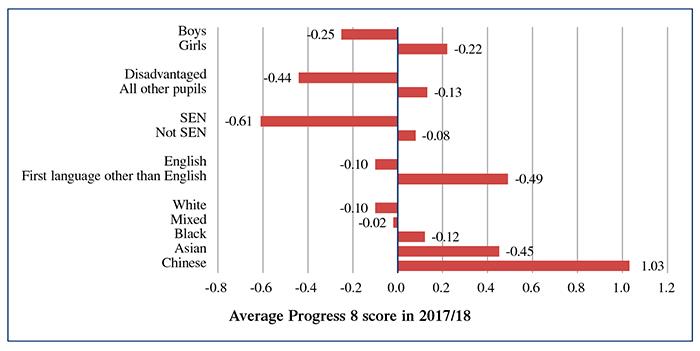

However, does it go far enough? There are some concerns that Progress 8 does not take account of differences in pupil demographics and socio-economic factors, which can vary substantially as Figure 1 (below) shows.

Figure 1: Progress 8 scores can vary markedly by pupil characteristics

Why should this matter to schools? Research shows that pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds achieve around half a grade lower in each subject compared to non-disadvantaged pupils with similar prior attainment.

Furthermore, disadvantaged pupils outperform their more advantaged peers on average in only six per cent of state secondary schools, which has not really changed since the introduction of Progress 8, despite the DfE’s official statistics for key stage 4 2018 (published January 2019) suggesting that the disadvantage gap is narrowing.

This has a disproportionate effect on schools with higher proportions of disadvantaged pupils on their rolls. Recently published research by Leckie and Goldstein (2018) suggests that more than a third of “underperforming” secondary schools would no longer fall into the category if progress measures were reweighted to account for pupils’ backgrounds.

A school having a low progress outcome that is reported in the public domain can potentially have other significant ramifications. For example, the school may be more likely to be inspected by Ofsted, which may pass an unfavourable judgement, or they may have difficulty in attracting and retaining new teachers and/or pupils.

An alternative viewpoint

There are therefore some strong arguments for refining Progress 8 to take account of differences in pupil demographics and socio-economic factors, but there is also a counter perspective to this.

One of the objectives of this and previous governments is to achieve higher levels of social mobility. The education system is one of the key levers that the government has to take forward this objective.

Ministers want to ensure that the right incentives are in place to encourage schools to close the attainment gaps that exist between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils, between pupils with SEN and those without, between boys and girls, between different ethnic groups, and so on.

If the DfE was to change the Progress 8 measure to control for demographic and socio-economic factors this could arguably weaken these incentives for schools to help their pupils achieve their full potential.

So what is the answer?

There is no perfect answer, but most people agree that Progress 8 is much better than the threshold measure used previously, as taking account of prior attainment is a much better basis on which to draw conclusions about the extent to which schools have contributed to pupils’ achievements at the end of secondary school.

That said, demographic and socio-economic factors do vary significantly between schools. In their research, Wilkinson, Bryson and Stokes (2018) suggest that these factors explain between 15 to 17 per cent of the variation in GCSE scores.

In addition, some of the large and persistent attainment gaps we see between, say, disadvantaged pupils and their more affluent peers may be due to other factors (e.g. home environment factors) which are outside of a school’s control. It therefore seems tough on schools with less affluent intakes not to take these factors into account in some way – and perhaps does not stretch “higher” performing schools in affluent areas sufficiently.

Various solutions have been proposed, including developing an adjusted Progress 8 measure that takes account of demographic and socio-economic characteristics or the proposal from the National Association of Head Teachers (September 2018) to only compare Progress 8 scores across school groups with similar pupil intakes to one another.

NFER believes that this is the time to take a fresh look at this to see whether Progress 8 can be refined so that all schools feel they are being more fairly judged in future.

- Dr Lesley Duff is director of research at the National Foundation for Educational Research.

Further information

- Pre-testing in EEF evaluations, Education Endowment Foundation, October 2013: http://bit.ly/2TvjiBk

- What impact does accountability have on curriculum, standards and engagement in education? Brill, Grayson, Kuhn & O’Donnell, NFER, September 2018: http://bit.ly/2LcdupK

- Analysis: The introduction of Progress 8, Education Policy Institute, March 2017: http://bit.ly/2TvjvEC

- Should we adjust for pupil background in school value-added models? A study of Progress 8 and school accountability in England, Leckie & Goldstein, University of Bristol School of Education, November 2018: http://bit.ly/2NKwRHt

- Assessing the variance in pupil attainment: How important is the school attended? IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Wilkinson, Bryson & Stokes, February 2018: http://ftp.iza.org/dp11372.pdf

- Improving school accountability, National Association of Head Teachers, September 2018: http://bit.ly/2yapeng

NFER Research Insights

This article was published as part of SecEd’s NFER Research Insights series. A free pdf of the latest Research Insights best practice and advisory articles can be downloaded from the Knowledge Bank section of the SecEd website: www.sec-ed.co.uk/knowledge-bank/