The challenging picture for music education in schools has been reported widely and featured in many articles in this magazine. We only have to look at the various ‘State of the Nation’ reports over the last few years to get a general picture. The pandemic presents even further challenges, the impacts of which we don't yet fully understand. Over the last few years, we at Royal Birmingham Conservatoire and Birmingham City University have been looking closely at publicly available A Level Music data, alongside other national datasets in music education, and have noticed some concerning trends that hold relevance to all of us.

A Level Music

Before we get into the nitty-gritty, we know that A Level Music is just one of many Key Stage 5 music qualifications. Though certainly not the perfect fit for all young musicians, it is appropriate for many – especially those who want to go on to study music at university whose interests are often not represented by vocational courses.

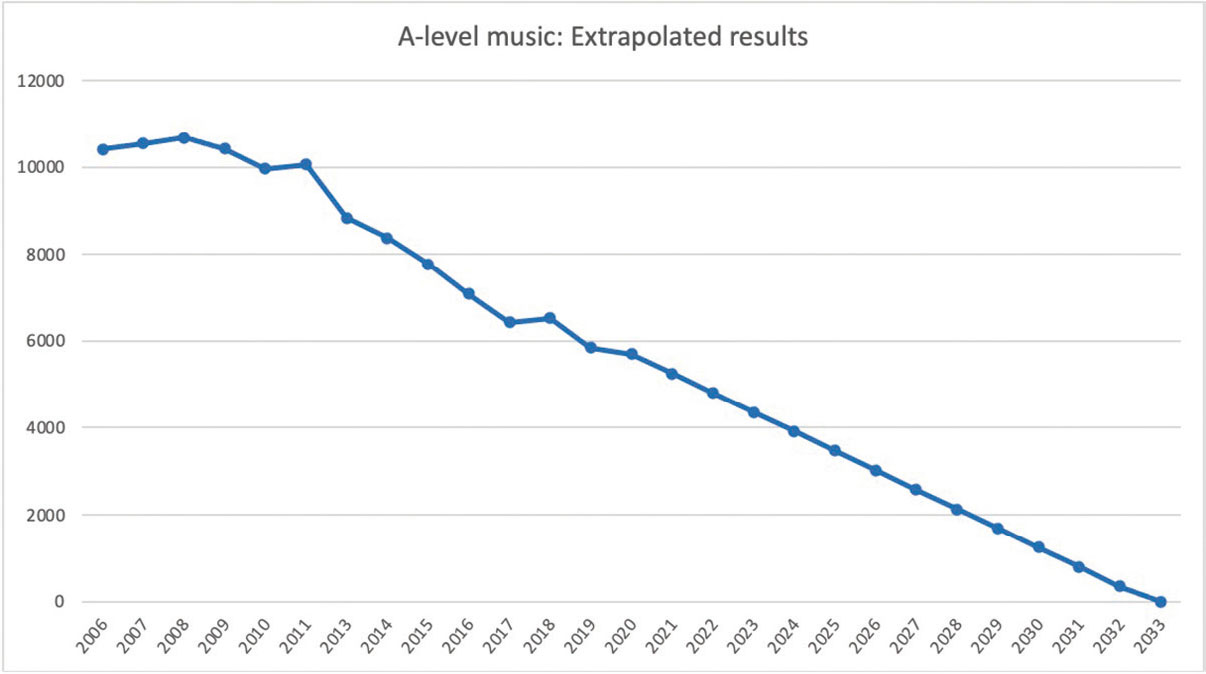

Over the past decade or so, the number of students being entered for A Level Music has fallen dramatically. In 2006 there were over 10,000 A Level Music entrants; by 2020, there were fewer than 6,000. This significant decline has happened bit-by-bit and year-on-year for the last decade or so. Its persistence is troubling, with the trend being one of gradual decline rather than a cataclysmic slump. As such, we wanted to see where this trend might leave us in a few years’ time and, somewhat dispiritingly, the results are something we should all take notice of (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Extrapolation of A Level entries in the years to come

Figure 1 Extrapolation of A Level entries in the years to come

Put simply, if the decline continues at the current rate, there won't be any A Level Music entries in 2033. This is just 12 years’ time. In reality, we suspect that such a point will be reached earlier as the qualification would no longer be viable in all but a handful of entry centres, or that it will exist as a highly exclusive qualification. However, taking 2033 as the figure for now, this means that these future A Level Music students are already in primary school, where, if they are fortunate, they might soon receive whole class ensemble tuition. If this is to be their first access to a musical instrument, how do they continue through to later stages of schooling? What does this mean for the pipeline of young musicians?

Squeezing of the curriculum

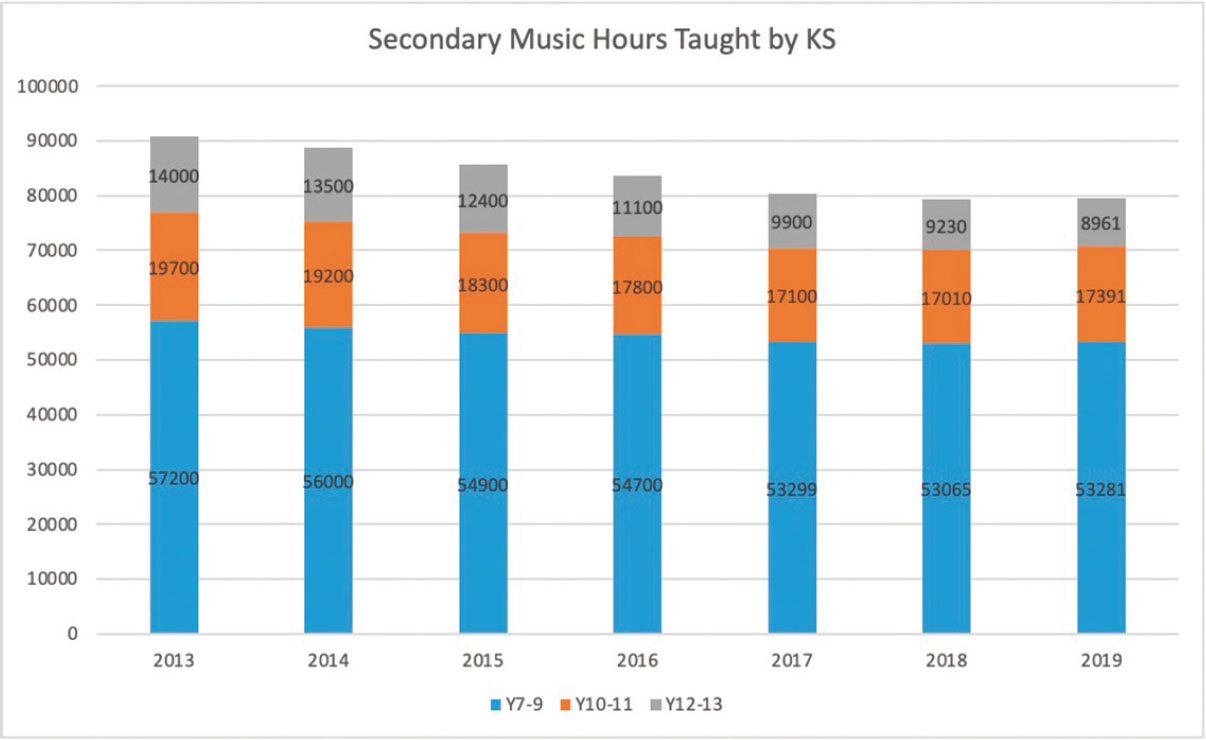

Although there is certainly evidence that music as a subject is under threat in many schools, it seems that the risk to A Level Music is more acute. Anecdotally, we know that many schools have minimum group size thresholds of between seven and 15 students; the national average class size for an A Level Music group is just over three students. Squeezing of A Level Music in school curriculum time can be seen in the number of hours of music taught at each Key Stage (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Number of hours of music taught at each Key Stage

Although there have been overall reductions in the number of hours of music taught, it is sixth forms which have borne the brunt of these shifts. Since 2013, the number of Key Stage 5 music hours has fallen by about 35 per cent, compared with a reduction of around 7 per cent in Key Stage 3, and just under 12 per cent for Key Stage 4. This is surely cause for concern.

Geographical disparities

These rather stark figures show an overall picture of decreasing access to A Level Music. We know that there are some local authorities without a single school or college offering A Level Music, and there are many in which just one centre offers the qualification. Even for a large local authority like Birmingham, where we are based, only 35 students took A Level Music in 2020. That is only 0.75 per cent of the A Level population. By contrast, Hertfordshire saw 154 students entered for A Level Music, approximately 2.2 per cent of the A Level population. Clearly, the demographic and socio-economic make-up of these two localities is quite different, and each has distinct challenges. However, we doubt that there are nearly five times more talented musicians in Hertfordshire than Birmingham! We are not singling these localities out, instead using them to illustrate disparities.

We suggest that this is evidence of a decline in access, rather than uptake, which impacts different parts of the country unequally. The reasons for this are complex but point to significant potential issues for the pipeline of young musicians and, importantly, the next generation of the music teaching workforce.

The fight for accessibility

Despite the complexity, this all boils down to a central problem; children cannot choose a qualification that is not offered to them. If only one school in a local authority offers A Level Music, what is that child to do if they don't attend that school or if they live a long way from it? If you are in one of those schools that is the only place offering A Level Music in your local area, don't give up the fight. Keeping A Level alive is allowing young musicians to choose a musical qualification that may be right for them.

With a national average of just three students in a group, use this data to make a powerful case for the reasons why A Level Music needs to be retained. Although as academics we are simply researching the statistics, as music educators we are concerned about their implications.

For up-to-date statistics on provisional A Level entries, visit www.gov.uk/government/statistics/provisional-entries-for-gcse-as-and-a-level-summer-2021-exam-series