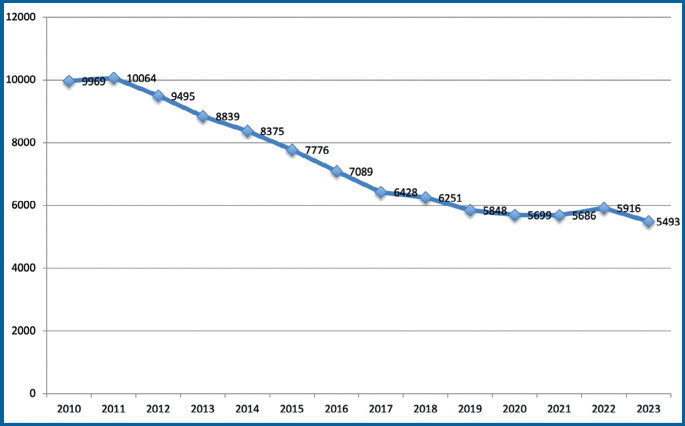

Back in the August 2021 edition of Music Teacher, we wrote about what we saw then as the possible demise of A Level Music in 2033. Little has happened since that time to make us change our minds on the general trajectory. Despite a slight uptick in entries last year – accounted for to some extent by a larger overall A Level cohort – 2023 has seen another drop in entry numbers, to below those of 2021. Figure 1 demonstrates this decline.

Fig. 1 A Level Music entries

Fig. 1 A Level Music entries

Shrinking class size

This downward trend is worrying for the profession as a whole, and deeply concerning for young people getting access to qualifications. The ramifications of this are widespread. Music teachers in schools may be presented with a minimum group size which they need to meet to ensure financial viability.

It may be helpful to note that in the 2021 Ofsted music research review the authors recorded: ‘It is notable that the number of pupils taking music A Level nationally implies an average uptake of around one to two pupils per school. This means that if a normal size school has five pupils opting for music A Level, the cohort is over double the average. It may be helpful for senior leadership teams to know this context and plan for the likely small class-sizes at Key Stage 5.’

Fewer teaching hours

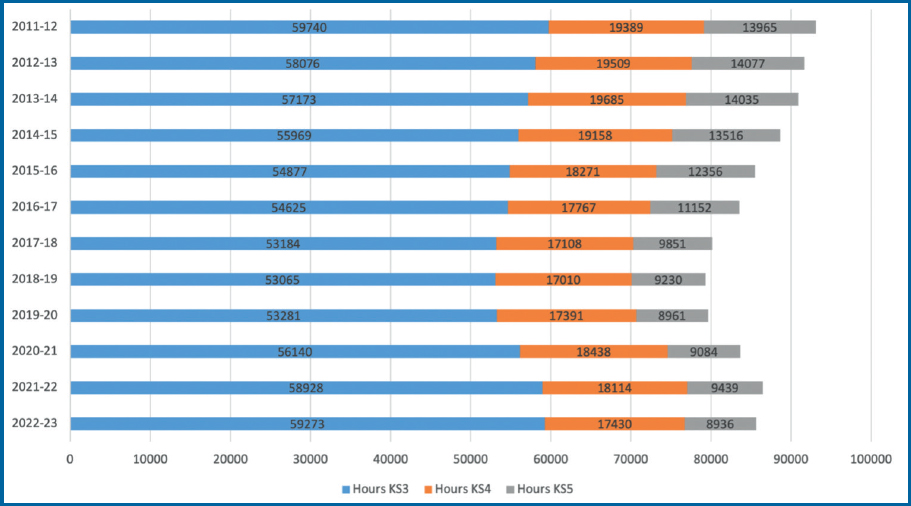

With decreasing numbers of pupils being entered for A Level Music, we know that there is a concomitant reduction in the teaching hours available for music at this stage. The number of hours for this has also been reducing steadily since 2011/12, as demonstrated in Figure 2 (see areas coloured grey); last year was at 8936 hours nationally, a reduction of some 36% in teaching hours over this timeframe.

Fig. 2 Secondary Music hours taught by KS

Fig. 2 Secondary Music hours taught by KS

KS5 reduction is matched by what is going on at KS4, where there has been a similar reduction in entries. It should be noted that as A Level entry often follows GCSE, then a reduction at KS4 is quite likely to be a good indicator of any knock-on effect two years later on KS5.

Variable grade outcomes

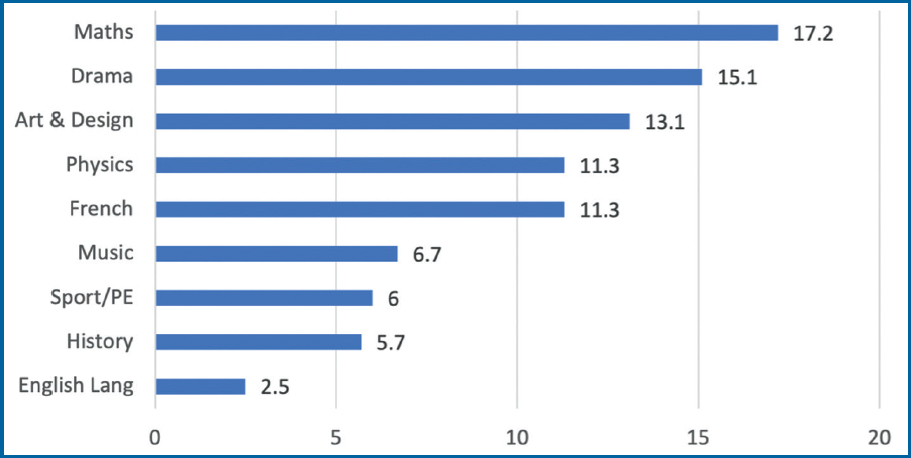

This year there has been another matter which is important: the percentage of passes at A* in A Level Music. The issue of comparability of grades across different subjects at A Level is a significant issue, and this can be seen by comparing exam outcomes of some popular A Levels, as in Figure 3.

Fig. 3 Percentage of students awarded A* (as %) at A Level

Fig. 3 Percentage of students awarded A* (as %) at A Level

What this chart shows is that Maths, considered among the general public as one of the most challenging A Levels, has nearly three times as many A* grades (by percentage) as music. The reasons for this are complex, and, as Paul Newton (2022) observes, ‘A Level standards are carried forward, from one subject exam to the next, by locating grade boundaries at marks that correspond to the same level of attainment, from one year to the next.’ While the reasons for this apparent anomaly are beyond the scope of this article, and involve significant statistical wrangling, nonetheless this is something else music teachers might need to be aware of if challenged on grade outcomes by SLTs.

Long-term effect

The implication of falling A Level entries, our main concern in this article, is that this will have significant ramifications not only on Music in schools, but on subsquent degree study. Whenever we point this out, we are told that the rise in Vocational Qualification (VQ) numbers will make up for any shortfall. However, from preliminary analysis of VQ data we believe that when comparing 2017 and 2022, there has been a 41% decrease in Music entries for vocational qualifications too.

As Music becomes imperilled in schools as a discrete subject, there are likely to be decreasing numbers of students willing to take the subject at university or conservatoire. This could well have an impact on access to the music profession in all its aspects (performing, production, creative and research) in the coming years.

As academics, we can only report on these issues. There will be those who will see this as an attack on teachers, and those that read this as an attack on curriculum. It isn’t either of these. We are reporting the statistical results from publicly available data. We will have to allow others to draw inferences and formulate action plans specific to their contexts and positions. But it is to be hoped this can be done rapidly, as that date of 2033 is getting nearer all the time.

References

Whittaker, A., and Fautley, M. (2021) ‘A Level Music: going, going, gone?’ Music Teacher. bit.ly/421jqre

Newton, P.E. (2022) ‘Demythologising A Level Exam Standards’, Research Papers in Education, Vol.37/6