In the frantic weeks following lockdown, the staff at Guildhall School worked long, fifteen-hour days, without a break, through the Easter vacation, in order to deliver a full online provision for all 1,100 of our Music, Drama and Production Arts students across Bachelor, Masters and Doctoral programmes. I stand in awe, gratitude and praise for my fellow team members who pulled together with such creative imagination and fortitude to deliver fully integrated online teaching and assessment provision. It was a huge undertaking as we all, in our various ways, came kicking and screaming into the online world. We learned the lessons that every school and university in the country has learned about Zoom and Teams, Moodle and Athens, and fair remote assessment – but there is more that we will take away from this crisis.

There is no doubt in my mind that all of our futures will be different, post lockdown, and that we need to design entirely new business models to deliver the changes we are facing. We learned that the received mantra of face to face equals good, online equals bad, was far from true or even a simple binary choice. There has been an astonishing array of positive feedback from both staff and students – some of it genuinely surprising, particularly given the wider sector discussion on value for money. Staff also report that students' learning focus has improved dramatically. Not having to commute or deal with the humdrum of life has given them more quality time to focus on their work. Their outputs have therefore improved – in both the depth of their reflections, as well as the quality of their work.

Of course, there are aspects of our very practical training that simply cannot be delivered online. But we learned that the online world has forced students to record their own performances to a far greater extent. While this was something that we had always encouraged, most students rarely did it, as, like most of us, they hated the sound of their own playing. It turns out that students recording themselves, in preparation for online lessons, has given them an enormous insight into intonation, rhythm and the whole architecture of a musical work. They have become much more attuned to their own qualities and shortcomings. Consequently, for some of them, their technical prowess and, more importantly, their artistic voices have matured in quite astonishing ways.

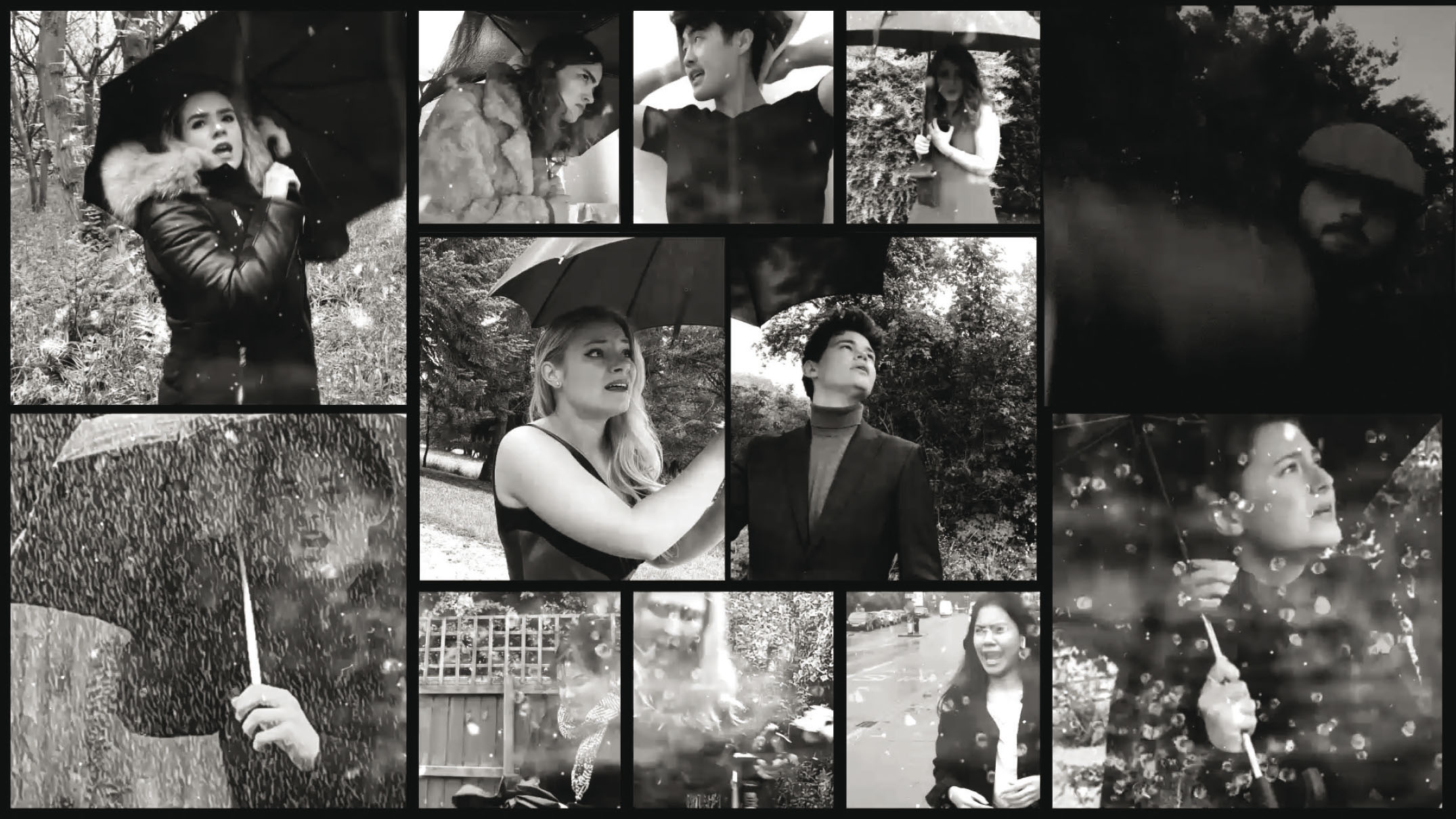

As I write, our Opera Department is working closely with Production Arts and BILD studios on an online double bill of Purcell's Dido and Aeneas, and Respighi's La bella dormente nel bosco. This will combine orchestra, continuo and singers all recorded in remote isolation from each other and lovingly stitched together, with highly innovative graphic artwork from our Production Arts Department. It has been a hugely challenging project that has strained every creative sinew, and required mind-expanding invention from its director, Olivia Fuchs and our own head of opera, Dominic Wheeler, in order to overcome some of the challenges involved.

So, these are some of the real benefits that we need to capture and take forwards when we return to some semblance of normality. However, there are also bigger artistic questions about productions and presentation of concerts to consider. What will the world of work look like when our students return?

I have a naïve optimism that some of the best of humanity that we have seen displayed during the lockdown will be preserved. The sense of generosity of spirit, where individuals step up, unselfishly, to help others with an awakening sense that we can all help heal our deep social rifts, through positive action, has never been more palpable. Artists and musicians all have a part to play. In the absence of live performance, many of my friends and colleagues have been asking the deep, existential, questions about what artists are for and where their place in society might lie. The loss of live performance, with its glorious sense of human empathy, is sorely felt.

Singing in the rain: scenes from Guildhall School's digital opera double bill

The Ancient Greeks did not think of music as a product-centred art form in the way that we view Western classical masterworks today; they saw it as a spontaneously creative process deeply rooted within civilisation. They believed it possessed a powerful moral, social and political essence, which was deeply expressive of humanity – an early form of artistic citizenship, if you like. We lost a great deal of that sense of civic responsibility under the influence of the aesthetic movement of the 18th and 19th century, but there has never been a better moment to reconsider its virtues. Our next generation of artists is ready to take up the call of artistic citizenship, to engender their own values and ideologies within their music and to reconnect with communities and the brave new world we all now have before us.

Singing in the rain: scenes from Guildhall School's digital opera double bill