In most scary films and TV series, music plays a quintessential role, without which, the audience's experience would be very different. In all genres – comedy, drama, romantic, adventure, horror etc. – music has a very particular role in supporting the story, helping with plot gaps, enriching the atmosphere, and drawing the audience's focus to particular things, characters, or situations. But what is it that makes a musical composition funny, dramatic, romantic, sad, adventurous, or even scary? In this article we'll be analysing the latter.

The unknown and the unworldly

There are two inclusive categories of situations that usually scare us the most, regardless of our age and gender, cultural background or ethnicity; I like to name them ‘the unknown’ and ‘the unworldly’. Their main difference is that with the unknown, we have no idea what it is, so we usually let our imagination fill the missing image, whereas the unworldly is something that we thought we knew but, in this instance, it appears with a heavily unfamiliar, distorted, or even unrecognisable form.

In a quick example, I like to parallelise the unknown with a completely dark room; we know that it is not empty because with every step we take we hear different noises, however we have no idea what might this be. The unworldly, on the other hand, is a room fully lit, full of things that we recognise but that are presented in an unusual way: imagine you walk into a room that is fully and normally furnished only to realise moments later that you are actually standing on its ceiling and everything is hanging from up high, including yourself. Creepy, right?

But, musically speaking, how do we recreate all that stuff using notes? It might be easier than we think, as long as we ask ourselves the right questions.

GCSE and A Level film music

While the four examination boards (Edexcel, AQA, OCR and Eduqas) offer a variety of composing brief options, in my experience the film/TV briefs are probably the most popular. This is likely to be due to our relationship with the medium, which is usually more intimate than with contemporary composing. Although slightly different, all exam boards base their briefs on a storyline and then ask the composer to compose a piece from the director's ‘point of view’. Therefore, it is important to ask the right questions before starting to compose, e.g. Why does this story need music? How high in the hierarchy is the soundtrack in this scene? What is the intended atmosphere? Is the music's role to hide/cover something or to reveal/emphasise it? These are only the starting points of the research we need to do before we begin composing, and even while writing the student may want to revisit them to make sure they are still composing the same piece they had initially started. There are many more practical questions which we will address below, mainly to do with the composition itself, including the soundscapes, timbre, texture and structure of the composition.

The orchestra

The classical symphony orchestra as a medium is usually our first thought. For sure, it offers a huge variety of timbres, pitch ranges and textures, and is therefore a safe go-to solution. However, many composers might want to explore different instrumental choices, from percussion and harps originating in parts of Africa, to south American plucked string instruments, and from Mediterranean wind instruments to Middle Eastern vocals (often sampled). The advantage of utilising some of these instruments is the relative – or absolute – unfamiliarity many people have with their sounds. (Imagine the eeriness of an echoey, atonal melody on a kora combined with some thin, high-pitched Mediterranean tambourine tremolo!).

© Shaineast/AdobeStock

Synths and sound designing

Electronic instruments are often the ‘usual suspects’ of a scary soundtrack. At this point we have to make clear that when we are talking about ‘scary music’ we do not usually include ‘jumpy’ scenes. There is an infinite number of ways you can make the audience jump off their seats and, usually, this is the job of the sound designer. Although our job as composers is to prepare the ground for this ‘jump’, usually these kinds of scenes have very little to do with music. In this article, when we talk about scary music, we mean purely musical ways to set a scary/creepy atmosphere within which the story will flourish and thrive. Electronic instruments and synthesisers are really good for sharp sudden sounds as well as producing very unfamiliar and mysterious timbres.

Harmony

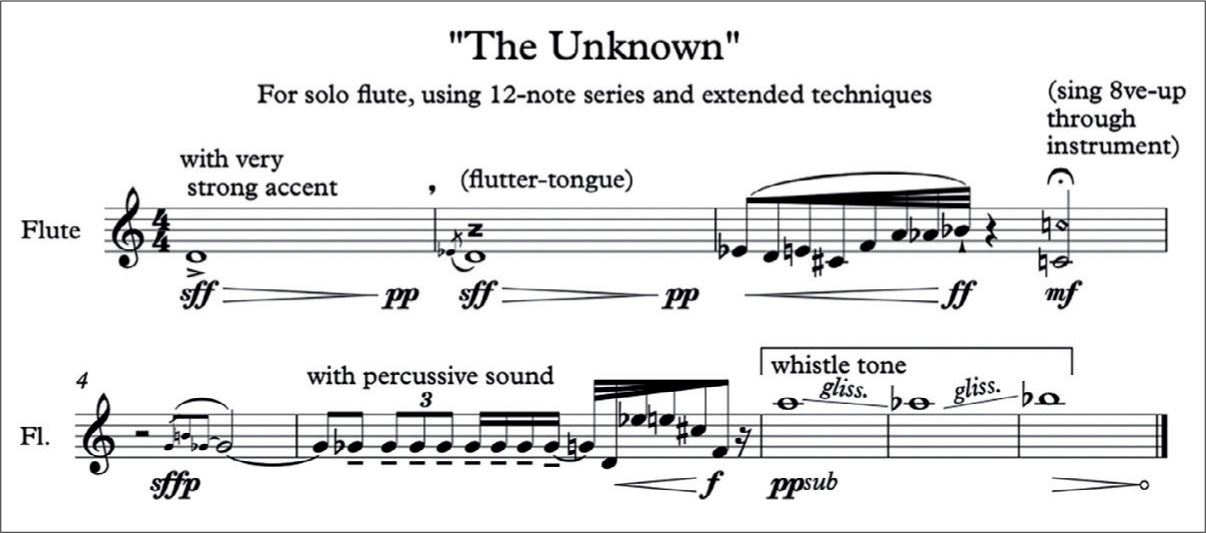

Particular modes have a quality that could potentially be very dark and unusual. Phrygian and Locrian, due to their rare start with semitones, are the best candidates. They also offer a convenient foreground for some nice chords, such as diminished, minor with flatted 5th or 9th etc. Another nice harmonic context is the 12-note system, which is my absolute favourite for scary/dark composing (Eliot Carter's string quartets will give you a clear sound of this), while quartal and quintal harmony (e.g. One Summer's Day by Joe Hisaishi), and Octachords (Oliver Messiaen's Catalogue d'oiseaux and Chronochromie are some representative examples) offer some useful palettes. The main characteristic which all the above have in common is the absence of absolute tonality. This provides flexibility and helps build tension.

Rhythms

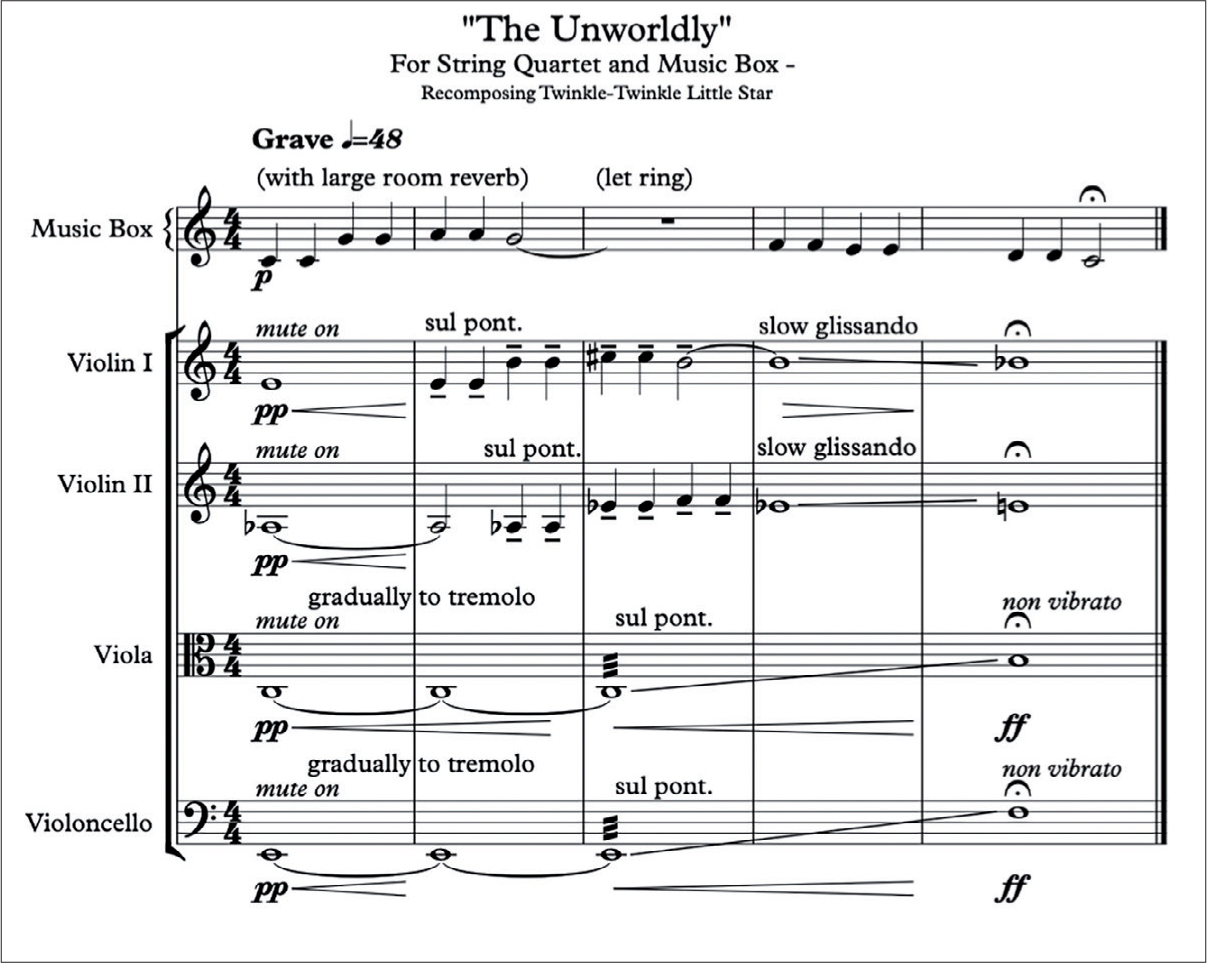

It is also suggested that we utilise odd measures (Stravinsky's Rite of Spring is a representative example of this), so that it allows us to build more complex and unusual melodies. We can also explore added rhythms (Bartók's String Quartets No1–3 are worth listening and reading for this study) and transform a simple melody into something more mysterious and unfamiliar. Also creating a free pulse piece is a valuable tool for building a dark atmosphere (Hildur Guðnadóttir's Joker and Chernobyl soundtracks are almost a ‘masterclass’ in this tool).

Instrumental extended techniques

Some of the most common orchestral instruments have the most uncommon and eerie sounding techniques. Woodwind: explore flutter and whistle tones. Brass: a variety of mutes and singing through the instrument. Piano and percussion: mute with hands, use fingers directly on instrument or use different materials to mute, such as paper, pieces of cloth etc. Some percussion instruments can also be bowed, like cymbals, vibraphone, marimba and so on. Strings: Try Sul Ponticello combined with tremolo. Some will say it is quite cliché, but it is an invaluable tool. Also, Col Legno Battuto produces an amazing effect – however if you are not using sample libraries, it might take a lot of convincing your performers to strike their strings with the back of their bow!

These are only a small sample of the extended techniques that are out there or can be invented to produce the sounds you have in mind.

Example 1. ‘The Unknown’ for solo flute, using 12-note series and extended techniques

Example 2. ‘The Unworldly’ for string quartet and music box – recomposing Twinkle-Twinkle Little Star

Here are a few exercises to which your students can start applying the above, as well as their own ideas:

Challenge 1. The Unknown

A) Create a melodic sequence/main theme that will be gradually moving further away from tonal/diatonic perception. It could be using the 12-note system, or another technique that may keep a safe distance from triadic harmony.

B) If the melody is purely monophonic, start thinking of the instrument that would depict best the scary mood you have in mind. Is it more ghostly (flute or clarinet?) or mysterious (oboe, bassoon, English Horn?) or maybe creepy (piano, strings?). These are only a few ideas and examples. If your theme is polyphonic, then either think of instruments that can play many notes at the same time, or small ensembles. What extended techniques do your instruments have? Can you affect the instruments' sound in a way that sounds unusual or unrecognisable? Be inventive and openminded. Explore your options. It may well be that these techniques will alter your initial idea; that is fine. As composers we must learn early on to not ‘get married’ to our ideas too soon.

Challenge 2. The Unworldly

A) Take a well-known melody, preferably non-scary (maybe even a nursery rhyme). Record it on your DAW and then start experimenting with harmony. Think outside the box and try reharmonising to a degree that some people would find dissonant. Try different instruments with a variety of pitch ranges and timbral differences. See what works best in making this creepy and unfamiliar.

Challenge 3. The Story

Develop a miniature piece based on a story line. You can make up your own story or get inspired by something you watched or read recently. How will your music help the plot develop, emphasising the scariness of it? Use the techniques learned in challenges 1 or 2. Ask the right questions: When you listen to the piece, does the imaginary scene ‘come to life’? Are you illustrating the right atmosphere? How could you develop this into a longer piece?

I hope the suggestions above can provide some useful material to encourage creativity and inspire composition students. Below are a few examples of the techniques mentioned above, as well as some listening suggestions.

Music notation examples

- ▶ Patterns with the use of added rhythm

- ▶ Eerie melody with extended techniques in Phrygian mode

- ▶ Reharmonising simple, well-known melodies

Suggested listening

Concert Music

- Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima, Penderecki

- Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, Bartók

- The Rite of Spring (‘Dance of the Young Girls’) Stravinsky

- Quatuor pour la fin du temps, Messiaen

Film Music

- Joker (Original Soundtrack) and Chernobyl (O.S.T.), Guðnadóttir

- Psycho (O.S.T.) and Vertigo (O.S.T.), Hermann

- Lost (TV Series) (O.S.T.), Giacchino

Footnotes

- Meaning all 12 notes are equal, therefore there is no dominant. Similar to Serialism, but without the absolute need to keep the notes in a specific order.

- Chords are being built upon perfect 4ths and 5ths rather than 3rds.

- Chords with eight different notes, usually including several chromatic clashes among them.

- Repeating a particular pattern but with an added element at the end, which alters the rhythmic pulse.

- Suggested reading: ADLER, S. (2002). The study of orchestration.