Michael House's 2017 documentary Braille Music is a film about music that just happens to feature exclusively blind musicians. Braille's story is told, starting from its origins in 18th-century Paris and finishing with the recording of a new piece of music, written, learnt and rehearsed in braille. My involvement in the film's production led me on my own journey of discovery and has deepened my appreciation of Braille the person and his ongoing legacy for blind musicians.

By the time Louis Braille was working on his music code in the 1830s, stave notation was already highly sophisticated. The 19th century saw composers increasingly eager to capture and prescribe on the stave every nuance of performance. Yet the musical world of Louis Braille was, by our contemporary standards, rather conservative. Braille's system has undergone refinement and expansion to cater for modern notation conventions, but the fundamentals remain largely unaltered. Braille's inner logic and portability have made it ideally suited to the digital age.

Before the end of the 19th century, braille music had been adopted across much of western Europe, where it opened up hitherto unnavigable routes into musical participation and employment, performance, teaching and, notably, composition. A direct lineage of blind organists, for example, may be traced from Louis Braille himself, through Louis Vierne, Jean Langlais, Andre Marchal to David Aprahamian Liddle. In the UK, the careers of Alfred Hollins and William Wolstenholme, founded on prodigious skills in braille music, would be the envy of any modern performer, blind or not.

During the 1930s, the then National Institute for The Blind ran a joint publishing venture with Novello, championing the works of blind composers in a monthly publication. Many compositions from the series remain in braille form only – a fascinating footnote of musical history awaiting rediscovery. It's inspiring, and deeply moving, to me that Joaquin

Rodrigo wrote the exquisite adagio from his Concierto de Aranjuez using a braille typewriter similar to the one next to me on my desk.

Sound to symbol

But it's easy to fall into the trap of talking about braille music as an impenetrable code understood only by a breed of mysteriously gifted individuals. Certainly, the invention of the code stands as a supreme intellectual achievement. Fundamentally, however, the journey towards musical literacy from sound to label to symbol is identical for both braille and print readers. What sets apart learning from braille music is the additional stage of putting down the music, holding the symbols in the short-term memory, processing the dots into musical sounds and then reproducing them on an instrument. These mental gymnastics requires a solid theoretical understanding, lots of practice and a good teacher – not to mention good coffee! But this is of course nothing new to anyone who has striven to sight-read print notation.

It is more enlightening to consider how braille music is typically used. I will usually study a score intensely until it is memorised. Thereafter, I may only refer to it for revision or in rehearsals. My opportunities for incidental learning and reading are fewer. I tend only to have access to scores I need to study and cannot browse in shops or libraries. This is an important factor when we consider young learners developing the skills noted above. Access to braille music is a perennial challenge, best illustrated through comparing approaches to the following common scenario.

Composer Zoe Dixon created a new work especially for the documentary Braille Music, performed by blind musicians in celebration of Louis Braille

Imagine you are a clarinettist asked to play a piece in a chamber ensemble. It does not feature in your personal collection, so you turn to the internet. You find several free editions to download but you need the same published edition for performance. You order this from a shop. You make your own rehearsal markings in pencil. You store the electronic version and hard copy version for next time. A familiar journey. Assuming I do not have the music either, my equivalent journey could take various routes.

Many braille scores are still produced and housed in dedicated libraries for the blind such as those in Paris, Copenhagen, Leipzig, Washington, and RNIB in the UK. I could browse their libraries online or email my request, and I may or may not hit lucky. Most libraries only offer hard-copy scores which I have no way of editing or marking up. I increasingly write out my own learning and rehearsing versions for this purpose. Here we are back to usage: the challenge of learning and memorising most orchestral parts has deterred all but the most intrepid braille music users, so there are few official transcriptions available. I could either turn to a transcription agency such as Golden Chord in the UK, or even ask a friend to dictate the music – sometimes the simplest solutions are the most effective.

Theorbo player Matthew Wadsworth: braille has opened up the ability to pursue a successful career in music

Alternatively, I could go online like everyone else. While collections such as ISMLP do not yet have downloadable braille, the potential of the internet to bring together the world's braille music collections under one roof has long been recognised. The Marrakesh Treaty, which came into force in 2016, makes legal provision for the sharing across borders of books and music in accessible formats without copyright restriction. This will eventually bring me a step closer to accessing music produced overseas, but my chamber music gig will have long since passed. So, I continue my search.

Making a difference

I then stumble upon the BrailleMUSE project, developed at the University of Yokohama. This unassuming website contains 1,100 scores of chamber and orchestral works which can be converted and downloaded in braille. It's worth reading this last sentence again. No pomp or ceremony, no viral social media activity, just a research project seeking to make a difference. I ponder briefly how that may have changed my musical career and make a note to learn the clarinet part to Beethoven's iconic fifth symphony, just because I can. If I find what I need, it's mine to download, edit, print out and store as I wish. If not, the quest continues.

The developers behind the world's leading notation software, MuseScore, have taken access to the world's music a step further with their OpenScore project. Right at the top of their list of reasons for undertaking such a monumental task is enabling access for anyone who cannot read regular print. The braille conversion element of the project is at a very early stage, but even partial success will transform the way we think about and use braille music for ever. It's a tantalising prospect, just as the internet was in the 1990s, or the printing press was to Gutenberg's contemporaries. Finally, I could use my GOODFEEL software to convert the music score I needed into braille. GOODFEEL, produced by Dancing Dots, was developed 25 years ago by a blind trumpeter who needed access to more scores more quickly. It's a remarkable achievement whose legacy is not just the braille dots, but the realisation it has planted in the minds of blind musicians that they can plan for almost-simultaneous access to scores. Theorbo player Matthew Wadsworth is one of dozens of musicians around the world whose musical livelihoods this enables.

But while technology provides the hope and the dreams, there is still something to be said for the convenience of a bookshelf and a piece of paper. For most of my life, availability of braille music has been my biggest concern. Now, the challenge is freeing up time and memory space to learn it all, and no technology can help with that. Time for more coffee.

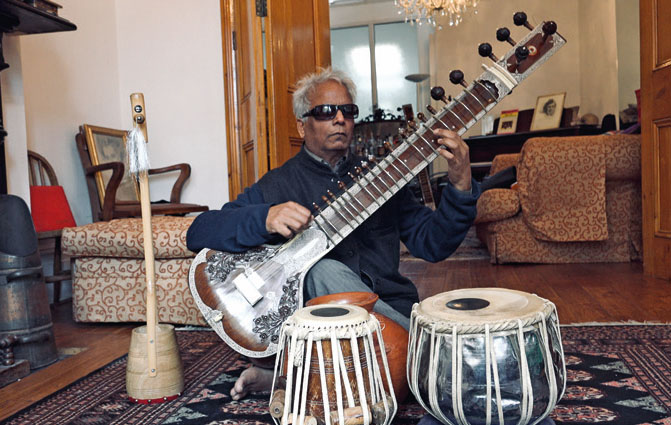

Forging music relationships across cultures: Baluji Shrivastav, founder of the Inner Vision Orchestra and a leading exponent of brailled music

James Risdon is a recorder player based in London. He worked for nearly ten years in the Music Advisory Service at the Royal National Institute of Blind People where he supported dozens of braille music readers, and offered advice and practical support to teachers, parents and professionals. www.jamesrisdon.co.uk

Michael House's award-winning documentary Braille Music: The story of Louis Braille's music code told by those he inspired is available to download at amzn.eu/aWfxMcj