According to Arts Council England, there are six In Harmony programmes (since 2008) across England, serving thousands of children most in need. Participating schools, working with professional organisations, commit curriculum hours and after-school time each week to ensemble music-making.

I met up with Jacqui Cameron, Education Director of Opera North (ON), who has long experience of In Harmony having worked also at the Sage Gateshead, and with Stephen Laidlaw, the In Harmony Lead at ON and a cellist and teacher on the programme. Laidlaw co-developed the curriculum, resources and lesson strategies.

Slow and steady

In Harmony ON started in 2012, with Windmill Primary School in Leeds. Since then it's absorbed five more primary schools, across Leeds and Halifax, and one secondary school, growing organically: ‘We never tended to go out and look for schools’, explains Laidlaw; ‘they came to us in a way that was manageable and sustainable.’ Schools saw and learnt from each other.

All pupils in Years 1 and 2 participate in weekly musicianship lessons, and in Years 3 and 4 they join a weekly choir. Years 3 and 6 also participate in small-group instrumental lessons. Some schools receive specialist SEN delivery, from a music therapist, and all participants have access to workshops and performances by musicians from the ON orchestra and chorus. Over the last 10 years, the programme has changed considerably; one of the main challenges has been how to scale up a model based on large investment in one school and a small cohort of children. But a firm goal has always been to maintain the quality and relevance for schools, while adding more and more children.

The schools contribute substantially in financial terms, which has been a barrier for some. On the other hand, those that join become firm partners and have high expectations.

Flexible design

To my mind, In Harmony ON's great advantage is its organisational design. There are bridges and pathways connecting aspirations and aptitude, and a pipeline that connects curriculum and after-school needs. The joined-up yet flexible system meets the needs of different schools. Crucially, it also invests longer-term in musical progression and creating bandwidth. ‘We make the access as varied and holistic as possible’, explains Laidlaw, which extends to using different pedagogies and outside specialists.

At secondary level, the provision is different since there are music specialists, of course, and an academic framework that hubs work to. ‘We’ll add in bits that the school can't do, like instrumental learning after school’, Cameron explains; but otherwise it's the school arts coordinator calling the shots.

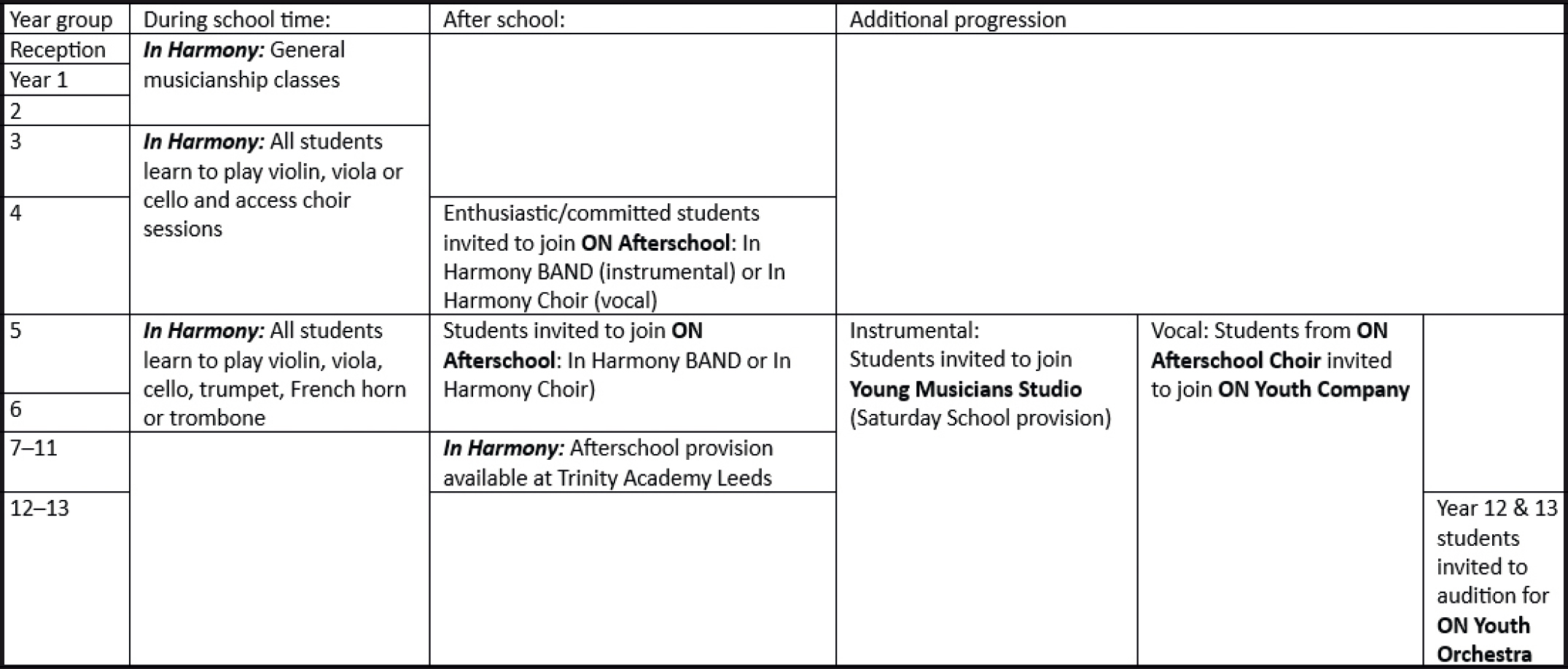

In terms of the pipeline, Cameron reports: ‘We are keen that young people who wish to continue with music follow the early years’ access. The In Harmony Band and Young Musicians Studio ease the transition to our Youth Company, which provides a clear pathway to higher music education. We are looking to ensure that young people have a chance to develop their musical skills regardless of background or previous exposure to music.’ For an overview, Laidlaw provided a helpful map:

Instrumental teaching

I ask how the teaching compares to other models (e.g. First Access) found in schools. For starters, groups comprise 15 pupils (i.e. half the class), covering three instruments. ‘It's a sort of mini orchestra’, Laidlaw explains, which is clearer when you realise that violins, violas and cellos form the mainstay. Also, the standard lesson has two specialist teachers: upper-and lower-string specialists. At the end of Year 4, students are given the choice to carry on with strings or switch to brass.

The big difference, though, is ‘how linked up subsequent years are, with some children accessing sessions consistently from Year 1 to Year 6’, explains Laidlaw; and for this, ‘a lot of my role is centered around making sure that there is consistency and a thread in the learning.’

He continues: ‘You might have a workshop that lasts one day or six weeks, or a whole term. But, theoretically, all our children can access 10–11 years of music education. That's something that we're keen to capitalise on because it's a lifetime's journey being a musician.’

Musicianship-based curriculum

At this point, I catch up with Elisabeth Brierley, the programme's EYFS & Key Stage 1 Lead, to ask about the importance of singing, a recurring theme. The programme puts Kodály at the centre of its curriculum, and singing takes a lead role in almost all sessions, whether musicianship, choral or instrumental. ‘This is because everyone has a voice – it's a universal instrument and one that we all access for free.’ She adds that understanding the concepts through singing prepares the groundwork for later instrumental work. You get the impression that there are no separate camps here.

The presence of Kodály also explains the resources and repertoire used, drawn from collections such as Singing Games and Rhymes (NYCOS) and Jolly Music. ‘Song-based repertoire’, Brierley explains, ‘means that all pupils practise reading and singing the material before starting to play it on instruments.’ Laidlaw adds how ‘Kodály is so well suited to working in groups’, underscoring this sense of continuity.

In the community

‘How a school is a doorway to its community’, Laidlaw confirms, is a real focus. Without doubt, schools have been a significant bridge to the wider community (and audiences), helped by strong ties at management level. Performances and opera have played their part in this. A small-scale production of The Cunning Little Vixen, involving three professional singers and an accordionist, was tailored to one school and then performed to children and parents. Another bridge is the ‘Big Sing’, which combines ON performers with schools from larger catchment areas, as part of a broader educational offer. The Water Diviner's Tale, for example, involved teachers and children learning songs in schools, followed by semi-staged performances across the north of England.

Sometimes there's more direct engagement and unexpected benefits. ‘We have a community residency in Richmond Hill (one of the most deprived areas in Leeds)’, explains Laidlaw, ‘that works with community members on activities with schools and involving chorus and orchestra. It's not the sort of thing we would have done at the outset; but it's happening and a lot of ideas come from the community. It's more co-created than we're used to.’

With a similar community-based project planned for Kirklees, I suggest, this direction must delight the Arts Council. There's no tension, however, Laidlaw explains: ‘A performing arts company in this country has to engage with the next generation and enthuse others about the arts. So yes, ACE is a driver, but actually we want the same thing.’

Where's the opera?

Thinking about where this all started, I ask how far the children are introduced to opera. Certain projects link to opera where there's clear educational value, as in a listening tool or to demonstrate what a project could become. But it also helps bring alive what's taught in class: ‘They become really interested with their instrument when it's seen in context, in a performance’, recalls Laidlaw. He mentions Mozart's Requiem, which, though not an opera, has provided dramatic references and cues for a composition project. It's also meant watching vocal soloists perform and taking note of whose instrument is playing when. Children are ‘fascinated by all sorts of things’, Laidlaw exclaims. For the large majority, this is their first encounter with an orchestra, let alone lyric sopranos.

In any event, talk of opera is missing the point. Completely. Children don't think ‘opera’, Cameron explains; ‘the idea that opera is not for them or is elitist is completely alien.’ What matters are the projects, the music-making and what, to me, feels like a social contract for ‘lifetime journeys’.