One of my character flaws is that I ask too many questions. I've always been like this, wanting to know more and wanting to know why. When I was a kid, I asked my piano teacher why I had to do Grade 5 theory. I received the stock answer: ‘in order to be able to do Grade 6’. I did it because I wanted what was on the other side of the barrier, but I didn't enjoy it. I didn't enjoy it because it was taught to me on paper, in silence, utterly detached from everything I love about music – sound, making it and hearing it.

Developing students’ specialist language and theoretical knowledge is an essential part of enabling them to function in the musical world, but it doesn't need to be a dry add-on. It can easily be woven into the fabric of all your lessons and rehearsals and, most importantly, contextualised.

Start from Year 7

This contextualisation can start with a melodic line that your students are familiar with as part of their performing and arranging work. Take, for example, a simple folk melody such as in Figure 1, which is packed with potential when it comes to developing students’ theoretical knowledge and musical language. I might open a lesson by asking: ‘How many bars in this phrase contain semiquavers’?

Figure 1: A simple folk melody that can be used as the basis for developing music theory and language

Figure 1: A simple folk melody that can be used as the basis for developing music theory and language

In asking this question, I am deliberately thinking about the explicit teaching that needs to take place for students to access the language I have used. In the opening weeks of Year 7, students are likely to understand nothing more than the fact they are looking for a number answer. When I ask a question like this, the number answer is pretty much the last thing I'm interested in. I'm using the question as a vehicle to widen and deepen students’ understanding and application of musical language – in this case, the terms bar, phrase and semiquaver.

Having illustrated and decoded the language as we unpick the question, I'm now able to use these specialist terms when I ask students to show me their work. I'm also trying to get to a place where students feel confident about using specialist language in context as they work with one another – ‘Let's try those semiquavers in bar 3 again’ – not because it sounds fancy or is going to enable them to pass a theory test, but because being able to explain and demonstrate things accurately and efficiently is endlessly useful.

If this melody were to crop up in our work at a later point in KS3, I might ask students to find me the moment where disjunct movement is used for the first time, as annotated in Figure 2. What I'm doing here is connecting the sound and physical stretch of the rising 5th with the relationship between different degrees in a scale, as a route into explorations of functional harmony.

Figure 2: Using the same melody to connect the sound of the rising 5th with degrees of the scale

Figure 2: Using the same melody to connect the sound of the rising 5th with degrees of the scale

Build on the fundamentals

You might take this simple folk melody and use it in performing, improvising and arranging work further down the line at KS3. Start a lesson, mid-project, by swapping out the B flat for a B natural (in other words, playing the melody in the Lydian mode) and you'll get a reaction. Use that reaction to begin an exploration of intervals, scales and modes.

Give students a different starting note and leave them to work out the phrase by ear, helping them connect the intervallic relationships that make up a scale or mode with sound. Workshop the melody starting on G and then C to start a conversation about the difference between a major scale and the mixolydian mode. This approach provides students with an interesting, demanding and musically immersive way of going about a piece of learning, and it is a lot more engaging and relevant than writing out lists of tones and semitones on paper.

Figure 3 shows a passage from Five Sheep, Four Goats, an arrangement by the Danish String Quartet of our same folk melody (published by Edition.S). Sharing this with students is an ideal way of developing harmonic knowledge, voicing, arranging and an understanding of simple rhythmic devices.

Figure 3: The melody arranged by the Danish String Quartet

Figure 3: The melody arranged by the Danish String Quartet

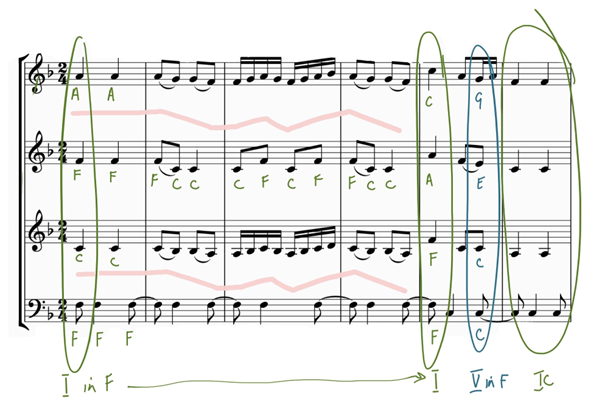

If my teaching focus was to develop students’ understanding of functional harmony and chord inversions, I’d probably change the alto/viola clef to treble clef for ease of reading, get it up on a big screen and annotate it in colour, as shown in Figure 4. Figure 4: Using the same arrangement to teach harmony (alto clef changed to treble)

Figure 4: Using the same arrangement to teach harmony (alto clef changed to treble)

We might play the outside parts and, with a fair wind, we might even manage the inside parts. As we work on it, I’d start talking about how this passage is built around a really simple tonic and dominant framework. I’d highlight the notes in the vertical stack of chord I, pick out the notes with my voice, and ask questions about the choice of pitches in the first four bars of Violin 2. I’d talk about the parallel movement and intervallic relationship between Violin 1 and Viola, and the rhythmic impact of the syncopated tonic and dominant in the Cello. Conversations might then turn to the second inversion chord I at the end of the phrase, why composers or arrangers might choose to do this, and the weighting of different permutations of primary triads. This might lead to discussions at GCSE on reharmonisations of returning passages in composition work, or on textural density, structural purpose, and idiomatic string techniques.

In conclusion

The long and the short of it is that there's no need for the false separation of theory and practice. Don't back away from using and explaining specialist language with your KS3 classes – but don't separate it from sound.