Say ‘music and movement’ and we automatically think about early years education. We think about action songs, circle games and puppets. We think about a phase of learning in which the important relationship between sound and the motion of the body is both well understood and explicitly taught.

Early years practitioners aren't the only ones to have made this connection. The interplay between the sonic and the kinetic is embedded within the language of professional music making too. To set a tempo of andante is to invoke the speed of a human stroll. The courante is defined by its running quality, a berceuse by rocking, and a barcarolle by rowing. We use these words as shorthand for the quality of movement that musicians have in mind when they compose, listen, or perform.

The elegance of an arabesque, the lop-sidedness of a ‘swung’ rhythm, the regularity of a ‘march’ – these musical ideas owe their distinctiveness to the physical gestures and movements they reference. Nor is this connection limited to rhythm. Colour might be the go- to metaphor for describing harmonies, but it's hard to talk about a melody without recourse to words like ‘float’, ‘slide’, ‘plunge’, ‘circle’, ‘bounce’, ‘jump’ or ‘step’. We describe our tunes using the vocabulary of human locomotion.

At secondary level, this connection is too often lost as the vocabulary of music shifts in a new direction. By focusing on what the national curriculum calls the ‘inter-related dimensions’ of music – specified as ‘pitch, duration, dynamics, tempo, timbre, texture, structure and appropriate musical notations’ – we adopt a technical view of performing, composing and listening which ignores the connection between sounds and the movements that create them. Concepts like ‘chord’, ‘key’ and ‘cadence’, however important they might be, conceal the fundamental idea of motion that underpins the creation of all organised sound. It's no coincidence, then, that a lot of secondary music education takes place sitting at a desk or stationery in front of a computer.

Curriculum planning for classroom music at Key Stage 3 tends to develop this technical, ‘disembodied’ approach by interweaving the three main learning strands – performing, composing, listening – through projects defined by their subject content, each entirely discharged within music as a self-contained discipline. While this seems justifiable where certain content areas are concerned, where it comes to others (dance music is the most obvious example), to learn in a purely technical and sedentary way seems to be missing a trick.

Activity 2

One project that lends itself particularly well to a more dynamic approach is music for film. Learning about, listening to, and creating music that accompanies on-screen images is surely one of the most popular of the projects that populate secondary schools’ KS3 and KS4 curricula. The scope for building students’ understanding of musical mood, character, the development of Leitmotifs, and how to amplify or subvert the meaning of cinematic images is enormous. Tasks which involve composing an accompaniment to visual stimuli, meanwhile, teach students to deploy musical devices precisely, to be alert to visual as well as auditory cues, and to perform with accuracy in the context of an ensemble.

So why not bring actual movement into this arena – or others – adding an extra layer of pedagogical depth to what is already a rich context for musical learning? Here are some ways in which a more dynamic approach can be taken in the music classroom in order to develop students’ awareness of the connections between their movements and the world of sound.

Activity 2

Gymnastics to Gymnopédie

Activity 1

If you haven't seen Andri Ragettli's viral parkour videos, they're well worth the Google search. The Swiss professional skier's inventive use of gym equipment showcases his balance, concentration and creativity, and students find watching him complete his seemingly impossible circuits highly compelling. Taking a short excerpt from one of these videos provides an excellent platform for students to develop body percussion pieces, augmenting the precision and variety of Ragettli's movements with a sequence of appropriate sounds performed as a looping soundtrack. Limiting the stimulus to a carefully chosen 10-second clip challenges students to render in percussive sounds the high-and low-impact jumps, bounces, springs, turns, balances and rolls that appear on screen. Both the limited duration and that fact that the clip repeats on a loop are important here, as these characteristics allow students to focus on the precision and quality of their chosen sounds.

Activity 2

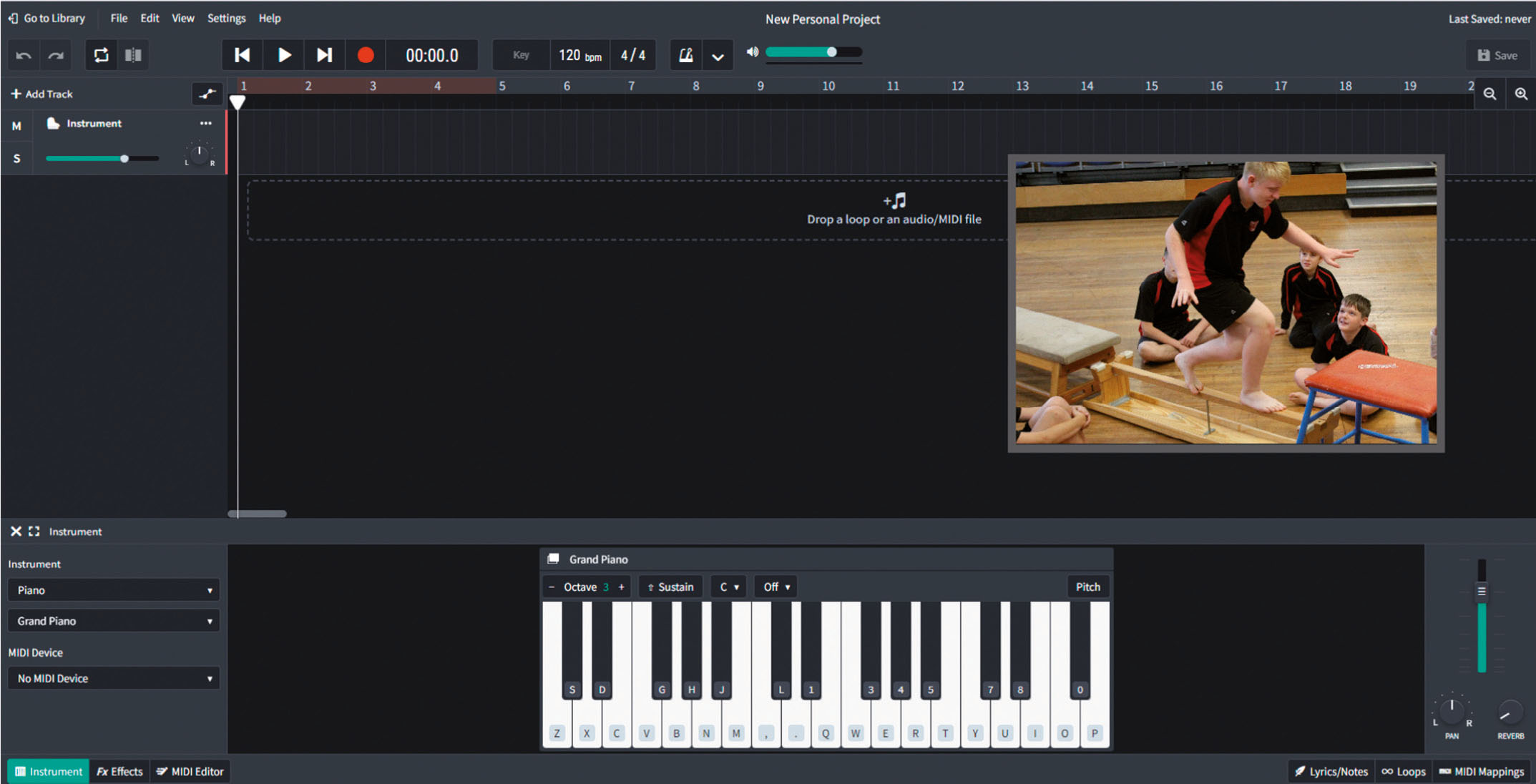

Hot on the heels of the quick-study body-percussion composition, an effective second task is for students to use the PE department's resources, and curriculum time dedicated to gymnastics, to work in groups to create their own sequence of movements, which they can film themselves performing. At the design stage, they should be encouraged to think about the sonic potential of the movements they make, building as much variety and interest into their sequences as they can. Typical sequences could include rolling, swinging, stretching, reaching, jumping and stepping, and might last up to around 30 seconds.

Back in the music room, students work with a midi-sequencer to create a soundtrack for the clip that they've produced themselves, using a range of musical devices, and matching visual cues as accurately as possible with sonic events.

Using a sequencer – BandLab in our case – rather than traditional staff notation applications like Sibelius makes it easier for students to stretch, reposition and realign their music with the pinpoint accuracy needed to create a compelling soundscape for the on-screen images. Students are free to use whatever musical ideas they like to build the track, save for two specifications. The first rule is that at least one longer, fluid movement must be accompanied by a musical device featuring a repeating cycle of four or five notes. The second is that at least one moment involving an unambiguous hit-point – landing from a jump, for example – should be matched with an accented chord cluster, the notes of which are carefully chosen to maximise the impression of the impact.

Activity 2

Activity 2

Activity 3

The relationship between music and movement can work the other way too – that's to say that we can use movement to understand how a piece of music works from the inside. In this next activity, students work in an open space, in pairs, each partner listening and moving to either the treble or bass line of a two-part piano piece, ideally played live by the teacher. Students hear the stimulus a number of times: first in total silence, next discussing what they've heard with their partner, and then – for as many more times as it takes to accomplish this final step – listening and creating a series of movements that represent, match and even illustrate the music they're hearing.

Watching other pairs performing their movement sequences is more than just a peer-assessment opportunity – it motivates students to listen more attentively to the musical lines and to critique more finely the way the movements match the sounds. In an imitative texture, are the motifs in imitation represented similarly by each person? Is the contrast between legato and staccato lines communicated kinetically? Are moments of separation and distance between the lines physically represented? Do the students show they've heard unisons and homophonic textures?

It's impossible to complete this part of the activity well without having listened to the music actively and analytically. It forces students to engage with the musical lines consciously, with the most successful students effectively memorising the musical detail in order to anticipate each musical gesture and produce its physical counterpart. Once the movement sequences are secure, two further stages are possible. Performing the movements without the music playing prompts performers and spectators to activate a collective musical imagination, effectively re-playing the piece in the mind's ear, with the movement sequence operating as a form of kinetic notation.

Activity 3

Activity 3

Activity 4

The second possibility – a further step of musical imagination that can work as a live activity but is even more effective when filmed – is to use the movements as a stimulus for an alternative musical composition. The ‘rules’ are run backwards now, with each gesture needing a sound and each sound required to match, as far as possible, the length, energy, and character of the gesture. Beyond that, the only additional rule, of course, is that what's produced may not use the music of the original piece.

If the performers have the technical skills needed to work individually, using two hands at a keyboard instrument, that can work well. Equally, the activity is well suited to a pair of barred instruments or any other instrumental duo. What emerges from the activity can be an impressively polished and well-balanced composition, generated in a fraction of the time that a conventional composing process would have taken. The results might have melodic and rhythmic similarities but it's surprising how far these shadow pieces can travel in diverse directions from the overall mood and spirit of the original. Depending on the scope of the project, students can record or notate these pieces, developing them into more elaborate and more ‘finished’ works suitable for submission as coursework, for example.

Activity 4

Activity 4

‘An ocean of inspiration’

Students respond positively to opportunities that combine their musical learning with physical activity and kinetic modes of thinking. Their evaluation of this approach emphasises the very different way that movement enables them to think about sonic landscapes. ‘Once you start thinking like this,’ one Year 10 student said, ‘there's a whole ocean of inspiration out there and it's almost impossible to get stuck.’

Activity 4

Activity 4

Unfortunately, this ocean of musical inspiration afforded by movement is not currently high on the official curricular agenda. It's an understatement to say that the current national curriculum for secondary music in England is a very short document. Covering a page and a half of text, the specification for Key Stage 3 breezes through the subject content of three years’ classroom learning in a pithy 120 words, eked out over six bullet points. Given their brevity, these words have proven surprisingly controversial. In the preamble alone, music is declared ‘a universal language’, aptitude for musical learning is referred to as ‘talent’, and teachers are enjoined to ensure students listen to ‘the best in the music canon … the works of the great composers and musicians.’

This provocation was deliberate. Three of the profession's sacred cows – our commitment to the social and cultural situatedness of music, our belief in the capacity of every student to develop as a musician, and our scepticism about placing too great a focus on the ‘great men’ of Western art music – had been sent off to the pedagogical abattoir. Such was the strength of the collective reaction to this opening salvo, the clear intention written through the remaining text received less attention from most quarters. The authors of the 2013 curriculum, unlike those of the previous iterations, wanted to steer teachers towards a technical rather than an embodied and dynamic view of musical creativity. They wanted us to sell our students a vision of music ‘created, produced and communicated’ using those ‘inter-related dimensions: pitch, duration, dynamics, tempo, timbre, texture, structure and appropriate musical notations.’

Something about this technical understanding of how music works is at odds with the way most music actually operates, and it's arguable that this is causing a distortion in the way in which classroom music education is delivered and received. Thinking about music as the sum of its component parts rather than as a social, cultural, and embodied phenomenon has disempowered classroom educators from making connections between music and movement. With a new iteration of the national curriculum surely long overdue, perhaps a more dynamic and lively approach might find its way into the documents.

Whether or not a more movement-friendly text emerges, it is open to practitioners to determine the emphasis and focus of our own curriculum design. With music as a discipline facing significant existential threats in many secondary contexts, building the cross-curricular potential of what we do might be an excellent way of building the connections that keep our subject alive.