Outreach is a dirty word. There's something very worthy about an outreach programme, which usually smacks of kids who have trouble with maths, or inner-city schools without playing fields being let loose on vast rugby pitches. In my department we're not very good at it, and we tend to leave it to other people.

But why are we so afraid of it? In a future of dwindling class sizes for music and battles over resources, could outreach be a way to pool our resources?

My usual battle, teaching music technology, is for any kind of suitable recording space. Finding quiet in the midst of the gentle thrum of the music department is only the start of the journey. Finding acoustically viable spaces; setting up the requisite screening, bass traps and deflectors to get a clean recording; arranging microphones and cables… all this usually takes the best part of my allocated recording time, leaving precious little time to put down any tracks. Add to the equation a group of students who are all keen to be record producers but far less keen to jump in front of the mics, and you have a recipe for the kind of frustration all of us have felt delivering classroom music at one time or another.

Like any teacher, I enjoy nothing more than a good moan. And it was during one of these moaning sessions that a chance solution to my problem popped up. A nearby college, I was told by one of the visiting instrumental teachers, had the opposite problem to mine – they had no music tech course. They did, however, run a highly successful and oversubscribed BTEC music performance course, but couldn't keep up with the sheer volume of recording required to satisfy the exam board. Added to that, the feedback from their latest external verification (for those of you lucky enough to have avoided this particular mini-Ofsted, it's like a tax audit but less fun) was that the quality of their recordings could be higher.

From idea to reality

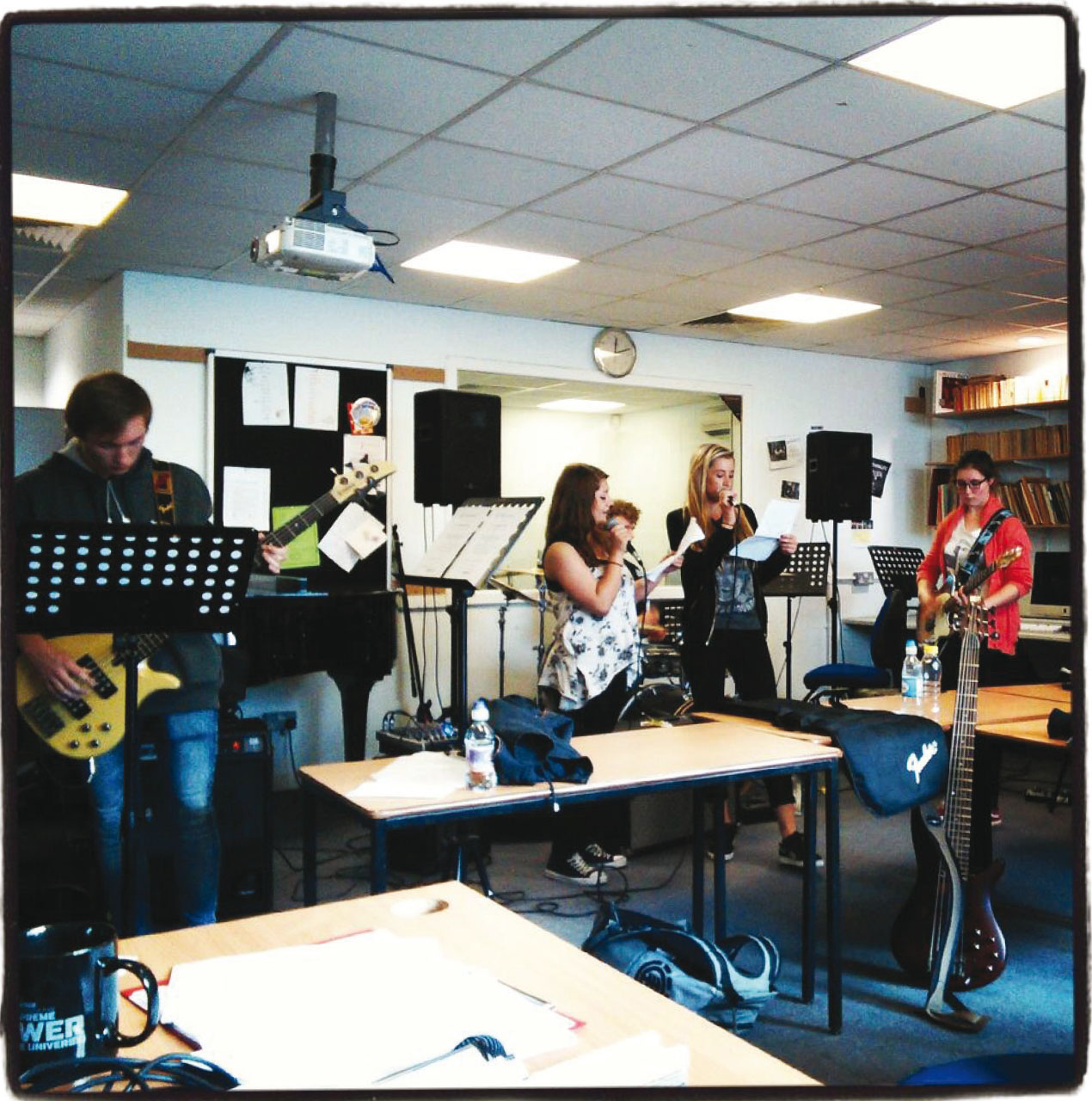

A few phone calls and emails later, the Mobile Recording Unit was born. On a cold January Sunday, my music tech crew loaded microphones, stands, homemade portable acoustic screens, a laptop and a small forest of cables into the back of a minibus and headed off down the road. The project was quite straightforward: my students would produce and mix recordings for three bands, all in the space of a day. The challenge for my team was to become instant producers and engineers, to capture the sound of a live band, and to get the best out of their players in a limited timeframe.

The challenge for the BTEC crew was to put on their best performances. There's nothing quite like the dynamic between teenagers to bring out the best, and potentially the worst, in each other. I would be lying if I said that I didn't feel a tiny bit nervous as we set off. What seemed like a brilliant solution to our mutual problems and a fantastic opportunity for inter-school cooperation now felt a bit like one of those crazy Saturday night ideas! No matter how much I had drilled into my lot that their responsibility as producers was first and foremost to get the best out of their artists without getting in the way, that level of social skill is something we just can't teach in a classroom.

The first challenge facing the Mobile Recording Unit was to work in an unfamiliar space. The school had a beautiful sound-treated hall, where we unloaded and started setting up our gear for the day. As soon as the first band started playing, we got a taste of just how nice the space was. The sound was bright and crisp, but not so buzzy that any recording would be stuck with the reverberation of the room on it. The great joy of recording is getting to make those decisions about how much or little of any effect you want on each individual signal. If you capture a recording in an overly reverberant space, that ambience will always be on the signal – whatever you do to it. Conversely, if the space is too dry (ideal for recording engineers) it can hamper the performance from the band – especially true of young musicians who may not have experienced playing in studio environments. The pressure of the microphone and red light is already enough, without introducing too many unfamiliar elements.

The second issue was taking on the role of producer with a group of unfamiliar musicians. Come across too forceful and you risk alienating your artists; too nice and you risk not getting the best out of the players. Before we set out, I gave my team a long talk on how to put people at ease and empower them to be their best. Finding the balance between quietly supportive and not willing to accept anything less than the best is hard enough with musicians you know; learning how to read a new group of performers, almost instantly, and work out the best way to motivate them is a skill many professionals still aspire to.

It certainly helped that the performers had the home field advantage. They felt comfortable and confident in their space and, with a little prompting, enjoyed taking on the role of guides. Simple questions, like where the loos are or where to find coffee (essential for any recording project!) became ice-breakers. This set the tone for the day.

Over an eight-hour session, the team put down two complete songs. For anyone unfamiliar with the recording processes, this is a herculean feat. A simple rule for tracking (the process of actually recording the sound, without mixing or mastering the final recording) is that it takes twice as long as you think it's going to, and then add on another hour for luck!

Putting it together

We started by putting down a guide track – all of the band playing to a click track. This is how they feel most comfortable and are used to working, and it produces the best foundation to build the recording on. Then, over the next few hours, we took individual tracks from each of the performers. This allows the producers to glue together the best bits of multiple takes, add effects to each part individually, and balance the parts to create a final mix.

The process of capturing each instrument is as much an artistic as a scientific process. Placing a mic on the sound hole of an acoustic guitar, for example, gives a completely different tone quality from placing a mic on the 12th fret. The producers and the artists had to work together to decide how to capture each track, what tone colours to prioritise, and how to compile the final takes into a finished multitrack.

The issue of sound and capture is a complex one. On the one hand, I would like to invest some time and resources into setting up an acoustically treated, functional space for my own teaching. This doesn't have to be prohibitively expensive. At its simplest, any room can be improved with some simple acoustic batting (display boards are surprisingly effective for this job), bass traps (pillows work well) and a bit of thought.

A previous bursar once told me proudly that the music department ‘isn't actually the most expensive in the college’, as though I was running for some kind of dubious honour. But I can't ignore the disproportionate balance between the number of students coming through my door and the resources and budget the department takes up. Adding the word ‘acoustic’ to a piece of equipment we need has the magical ability to add 50 percent to its price – although explaining to a resourcing team that the piece of sponge you want to stick on the wall has been designed by a specialist in acoustic engineering, with decades of experience transforming the sound of spaces, is probably harder than simply tacking some of the more intransigent bean counters to the wall (they make surprisingly good diffusers!).

The Mobile Recording Unit in action

The balance I have to achieve is between being wasteful with wider resources, and ensuring that my students learn to do the job properly. It's impossible fully to appreciate the impact of good and bad acoustics until you have experienced them first hand. It's impossible to appreciate a recording engineer's job until you have spent hours trying to correct a take with the noise of a building site in the background of the recording. And it's impossible to appreciate the benefit of this kind of project until you see the look on the students’ faces when they play back their final tracks.

The best bit of the first outing of the Mobile Recording Unit, for me, was seeing my kids work as adults for the first time. It's easy to forget that these young people whom I can occasionally squeeze an essay out of – and I'm all too guilty of seeing them as the sum of their assessment criteria and learning needs – are in fact human beings. Not the musicians and recording engineers of tomorrow, but the musicians and engineers of today. Within an hour, the initial shyness brought about by nerves and teenage bravado had evaporated into a precious young professionalism. My kids wanted to get the job done, and all they cared about was getting the job done well. I was particularly impressed with how easily they fell into the roles of producer and artist – coaxing the best out of each other, and judging and finding those boundaries as skilfully as many more experienced players. Likewise, the performers quickly switched mode from show-off swagger to engaging their ears and making decisions about how they wanted their final recordings to sound.

Good vibes all round

If I was left with any doubt about how successful the day had been, it was blown away at the last play through. After carefully capturing the recordings and slicing together dubs and overdubs, we produced a simple stereo mix for final inspection. The process of mixing is a science/art all of its own, and requires patience, imagination, taste, flat frequency response headphones, a range of playback devices, and some more patience for good measure! As the team crowded around our hastily-set-up monitors to hear the fruits of their labour it only gradually dawned on me that they weren't arranged in schools any more – the groups had merged, becoming one big team bound by shared music-making.

I am fortunate to have both a good basic music technology set up and an eternally patient head of department who is willing to let me run with some of my crazier ideas. The first outing for the Mobile Recording Unit was a success. All it cost was the petrol to get the minibus down the hill and back again. I am indebted to my partner school for going along with the idea, and to the kids for giving up their time. What they got out of the day was so much more than I could have given them in either time or resources.

Is this approach worth the effort involved in setting it up, the sleepless nights worrying about the learning outcomes and measurable objectives, and the inevitable rejection and diary frustration of trying to set it up? On the evidence of the first outing I have to say yes, although I do admit that this was as smooth as I could have dreamed of. While this may not always be the case with future ventures, the Mobile Recording Studio is a creative solution to the unavoidable problems of resourcing and budget constraints. More importantly, it is an opportunity for my kids to work as professional musicians.