Social isolation, inactivity and lack of outdoor play: this was the bleak reality facing many children’s lives during the heights of the pandemic. With playgrounds out of bounds, nurseries shut and play dates banned, the effect on children’s mental and physical health was likened to a ‘ticking time bomb’.

But the upshot of the pandemic is that it has given the world a glimpse into what an unhealthy childhood looks like – and hope for a future where children’s right to play outdoors, freely, is rightfully restored.

Fresh air; connecting with nature and engaging in adventurous play are now high on the list of priorities for parents when choosing a nursery place for their child. Forest School and outdoor learning have seen a rise in popularity, and settings are investing in their outdoor areas, equipping them for risk and challenge.

Anita Grant, chair of Play England and chief executive of Islington Play Association, says, ‘Never has it been more important to facilitate children’s outdoor play. Nurseries have a massive opportunity to be fundamental to creating access for risk and challenge for children in a safe way. Practitioners should be brave and use risk-benefit assessment to widen the experiences of children who have been more restricted than ever before during two years of pandemic response.’

SHRINKING WORLD

Over the past few decades, there has been a substantial decline in the amount of time children are playing outdoors. Today’s children are 11 by the time they are allowed to play outside unsupervised, which is two years later than their parents, according to the British Children’s Play Survey published in April 2021.

One of the main reasons for this is the increased emphasis on keeping children safe – from increased traffic and strangers.

‘The concerns we have from this report are twofold,’ explains Helen Dodd, professor of child psychology at the University of Exeter. ‘First, we are seeing children getting towards the end of their primary school years without having had enough opportunities to develop their ability to assess and manage risk independently. Second, if children are getting less time to play outdoors in an adventurous way, this may have an impact on their mental health.’

Public playgrounds are the number-one location for children’s outdoor play, according to the survey, but access to public play spaces in the UK is unfair and unequal. The Association of Play Industries (API) found that London has the second-worst play provision in the UK with 866 children per playground, whereas Welsh children enjoy access to more than twice the number of playgrounds than children in London.

Add the pandemic to the mix and the outlook for children looked so bleak in 2021 that campaigners launched a #SummerofPlay campaign to help get children of all ages playing out.

Dodd, who is running a seven-year research project looking at children’s adventurous play as a mechanism to reduce anxiety, says, ‘When children play in an adventurous way – climbing trees, riding their bikes fast downhill, jumping from rocks – they experience feelings of fear and excitement, thrill and adrenaline.

‘We propose that when children have plenty of opportunities to experience these sensations in a non-threatening way, and to learn that they can cope, this will protect them from becoming overwhelmed by anxiety when they are faced with a situation that is scary or uncertain.’

FREE PLAY

Early years settings and childminders are working tirelessly to offset the devastating mental and physical toll that lockdown placed on the children in their care.

One way that they are facilitating recovery is through supporting children’s right to free play, whichis central to early years practice.

According to Play England, free play is defined as children choosing what they want to do, how they want to do it and when to stop and try something else. Adults only join in as and when they are invited, and the child leads the play. Grant says, ‘It comes from a deep place where their brains are exploring their surroundings, finding things out and making new connections.’

This type of play can be indoors and does not need to be adventurous, but when children are given the space to choose what they want to do, they will naturally explore different feelings, including adventurous, exciting play. Being outdoors facilitates adventurous play, especially in nature.

EQUIPMENT AND RESOURCES

A well-planned and equipped outdoor area offering a range of physical challenges provides an excellent space for children to indulge in free play.

A well-planned and equipped outdoor area offering a range of physical challenges provides an excellent space for children to indulge in free play.

Open-ended materials and loose parts are great for supporting this type of play. For example, old tyres can be used in different ways where the risk level can be adjusted to suit children’s abilities and needs. They can be stacked up, climbed up and jumped off, or a child can lie across the inside of them while being rolled along. Resources for building dens, wheeled toys, structures to climb on and jump off, water, mud and sand play are all great for fostering children’s independence.

Because of their open-ended nature, loose parts allow children to set the challenge that is the right level for them.

Dodd explains, ‘They only build a tower that is a height they want to climb to, or they only build a den that has the right balance between safety and adventure. With fixed equipment, that adjustment by the child to their own level is not possible.’

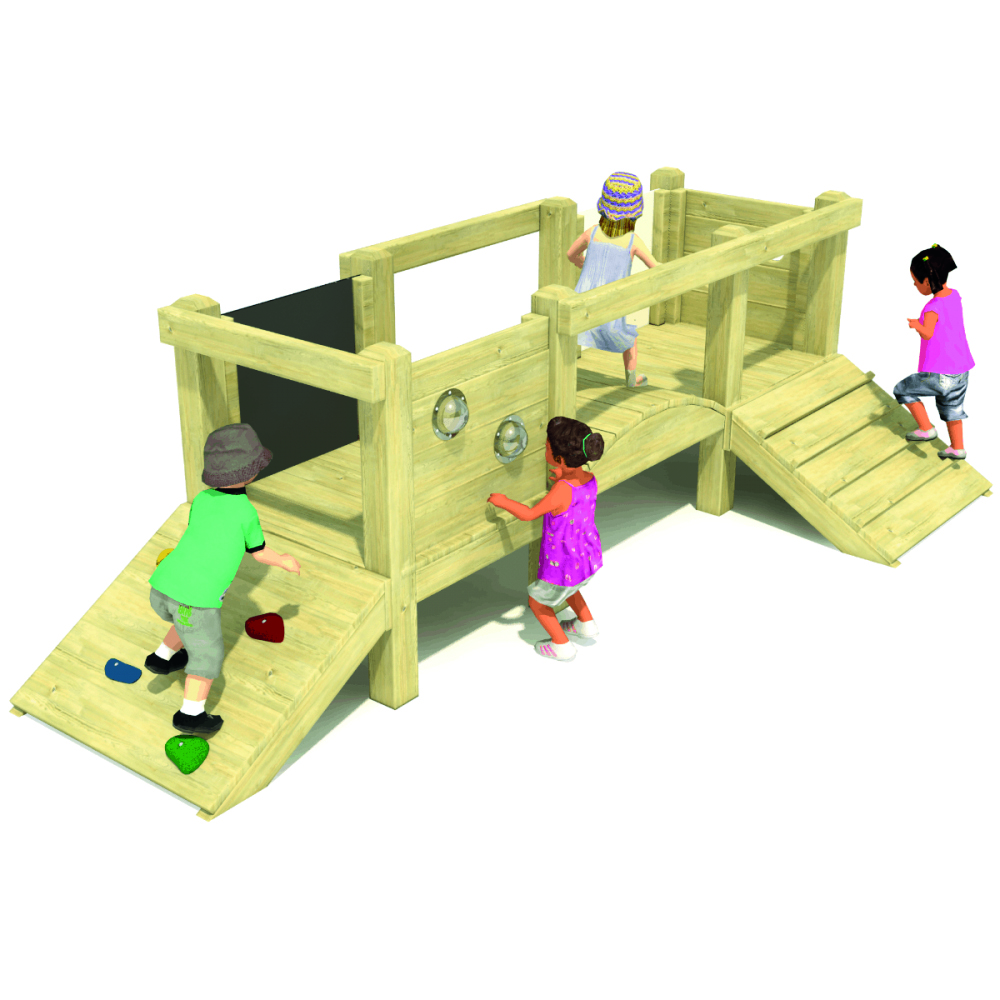

Large play equipment, particularly structures that allow children to play at heights, climb and jump, is important for children’s physical development and offers opportunities for adventure.

However, Dodd warns, ‘Large equipment can be expensive to install and if it isn’t particularly well-designed, children tend to play on it in a specific way so it doesn’t necessarily support open-ended, creative, free play. For the same money, a range of resources could be provided that give children choice and support creative, free play.’

Here are some examples of how nurseries are using large and small equipment and activity programmes to promote outdoor, adventurous free play:

All the elements

Islington Play Association runs Paradise Park Children’s Centre nursery, a free-flow, free-play setting incorporating an adventure play ethos into the offer. They have all elements in the outside area: a fire pit, water play and tree walkways.

Grant says, ‘The essential impact of children experiencing the elements – fire, air, water, earth and wind – can form the basis of any outdoor offering, building on what has been historically and globally recognised throughout human life as fundamental to our experiences in the world.’

She urges practitioners to be brave, make use of risk-benefit analysis and find examples from all over the world of how to incorporate risk, challenge, creativity and self-reliance into children’s lives which will help with anxiety, nervousness and self-confidence.

She adds, ‘Forest School is an overarching term for children learning outside – every nursery should adapt the core aims of freedom, connection with the natural world and child-led, choice-based opportunities for their own setting. We would like to see practitioners confidently arguing for their own outside-focused approach.’

Landscaping in Scotland

Wiktoria Cook, senior landscape architect for Wardell Armstrong LLP (@WALandscape), has been involved in the redesign of up to 50 outdoor areas in public nurseries across Scotland in the run-up to the roll-out of the 1,140 hours of funded childcare.

She says, ‘Our designs follow a child-centric principle, bringing natural elements and “playable” landscapes in place of the often costly and prescriptive equipment which can be seen in many formal settings.’

The designs feature wooden posts with metal hooks, which have multiple uses, including: hanging decorations from; making dens and shelters; hanging ropes across to make musical structures; or clipping on detachable swings. Large sandpits are also incorporated into the play areas, with cleverly designed edging made from staggered wooden sleepers so that children can practise balancing and co-ordination. Tree log seats are dotted around the sites, which children can use to jump over and off; make small-world play surfaces on, and sit on at circle time.

While large and more formal play equipment certainly has its place in nurseries, Cook says, ‘It doesn’t always invite the same push to come up with your own games, requires much stricter maintenance and comes with additional restrictions in terms of big fall zones and safety surfacing.’

She adds, ‘Nursery settings benefit more from equipment at small to medium scale combined with loose parts which invite children to think outside the box and work together to create. This also allows young children to play largely without assistance and build their confidence through risk and challenge. The staff and pupils are welcome to deck the playground out with loose parts that suit them; popularly, mud kitchens, den-making elements, bird feeders or water and sand play.’

Large equipment, freestanding

Sovereign Play’s Beech Freestanding Adventure Playground Tower, £1,254, features a sloping stepped platform encouraging balance; a slanted bridge and steps. There is no need for surfacing onto tarmac or grass due to the tower’s low fall height. Orders over £200 receive a free box of Odd Blocks, £19.95.

Children aged three-plus will enjoy climbing up TTS’s Wooden Climbing Prism, £1,300.

For jumping and climbing fun, try Cosy’s Jumping Off Slope, £96.99, or its Kendray Cube, £285 (below).

Community Plaything’s Outlast Toddler Climbing Set, £1,300, supports gross motor skills with age-appropriate challenges; it also offers the Toddler balancing set, £346.

Loose parts:

Cosy Direct’s Gigantic Pipe, £282, can be used to roll around inside, crawl through, or it can be fixed to a slope for a tunnel slide.

Create layouts for children to walk along with Early Years Direct’s set of 6 Balancing Logs, £185.

Make a simple den kit with Muddy Faces’ Explorer Den Kit – Adventure, £47.51.

Create obstacle courses with crates, planks of wood, tyres and cable drums, with Cosy’s Complete Loose Parts Panacea, £546.

Forest School – ‘risk is holistic’

Nic Harding, projects officer for the Forest School Association (FSA), on why Forest School ticks all the boxes when it comes to providing children with challenging, adventurous free play.

‘Forest School (FS) provides huge potential for imaginative, free and adventurous play. Climbing on logs; using tools, rolling in mud; building structures; going on quests; making swings; playing with ropes; climbing trees; using pulleys and playing with mud and water. Appropriate risk taking is a huge part of Forest School. The overcoming of vulnerability from getting dirty, picking up a worm, climbing a tree or lighting a fire with a flint and steel increase children’s confidence and, through repetition, expansion and trial and error, produce resilience.

‘Risk is also holistic – and so is adventure – and it includes social, spiritual, emotional, intellectual and co-operative risk. Testing opportunities through exploratory, imaginative or adventurous play helps children face their fears piece by piece in a safe environment. As adults we might look at children walking a log again and again as repetitive or even mundane. For that child it is risky, fun, scary, difficult, high up, rough, wobbly or knobbly. Every step is a complex balance of physical, emotional and social risks. After they jump from the end of the log into the mud, they experience euphoria, confidence and the desire to do it again.

‘FS leaders are always looking for new opportunities to raise potential and progression for exploration, in line with the intrinsic motivation of the child. For example, moving from log balancing to tree climbing and then on to slack lines. The goal is for children to self-regulate their feelings of vulnerability and increase their confidence and resilience by testing and retesting their experiences. Regular sessions allow the child to apply the experience to other settings – at home, with siblings, in nursery, with grandparents – and to practise their newfound skills and confidence before returning to the source of the exploration and building on the experience. One-off, short term or curriculum led outdoor education or FS-like activities do not allow this exploration, typically.

‘We know that all forms of appropriate risk-taking are fundamental as a motivation to learning, growth and development. Remove risky play or the spirit of adventure and you may never see a child’s full potential and may condemn the child to a lifetime of anxiety and self-doubt that no amount of English, maths or science can cure.’ Harding is a qualified Forest School leader and one of the authors of the new book, Growing a Forest School from the roots up!, available from the FSA at £29.99.

MORE INFORMATION

- FSA: https://forestschoolassociation.org

- British Children’s Play Survey: https://bit.ly/37mbHgX

- Unequal access to outdoor play: https://bit.ly/3vX1EJm

- Summer of play campaign: https://bit.ly/3hWxNbO