Throughout history, musicians have used different kinds of shorthand simply to save time. In the Baroque era the language of figured bass – where the numbers (figures) dictated the diatonic intervals to be voiced above any given bass note – allowed composers to draw upon the improvising skills of the performers to generate the sounds they needed.

In jazz, pop and other related music, the language of chord symbols fulfils the same function but there is a marked difference between the two harmonic languages: one is largely diatonic and guided by the key-signature, while the other is more chromatic and independent of key.

Musical shorthand was largely abandoned during the chromaticism and Romantic works of the 19th century, and it wasn't until the popular music of the 20th century that a new system of shorthand emerged. The new chord symbols that appeared in widely published songbooks were entirely independent of key signature and became the foundation of the jazz harmony we know today. The sheer amount of music that is available in this format means that there is an enormous repertoire awaiting you once you start this journey.

The basic chord symbol

Unlike classical harmony, where we normally begin with triads (major, minor, augmented, diminished etc.) and their inversions, in jazz harmony (as used to harmonise the 'American Songbook') the basic unit is a seventh chord… this being the symbol that uses the least ink!

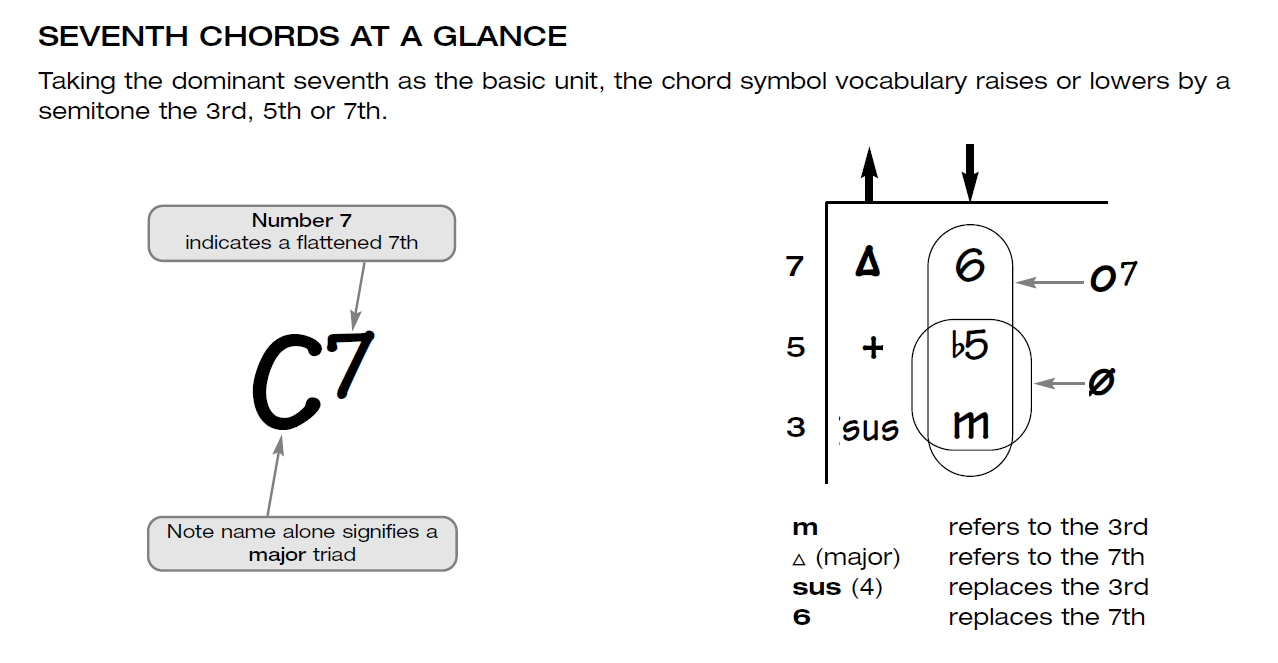

The note name indicates the major triad, and the number 7 indicates the 'flattened' 7th (as opposed to the seventh note of the major scale). Therefore, G7 is a chord of all white notes: G, B, D, F.

From here it is possible to raise or lower the 3rd, 5th and 7th of this chord by a semitone simply by adding the appropriate symbols. The diagram below shows the possible permutations effecting small changes to the seventh chord.

Notice that there are a couple of shortcuts. If you wish to flatten the 3rd, 5th and 7th of your G7 chord, you can use 'G07' (G diminished 7th) rather than writing Gm6b5! Likewise, if you wish to flatten the 3rd and 5th only, forming what is considered the 'half-diminished', then you would write 'Gø' instead of Gm7b5.

Here is a list of different seventh chords (in no particular order) that can derive from a basic G7 chord (using the diagram below):

G7+, G7sus, GΔ, Gm6, Gø, GΔ+, GmΔ, G7b5, GoΔ

© 2003 ABRSM. Reproduced with permission from The AB Real Book

© 2003 ABRSM. Reproduced with permission from The AB Real Book

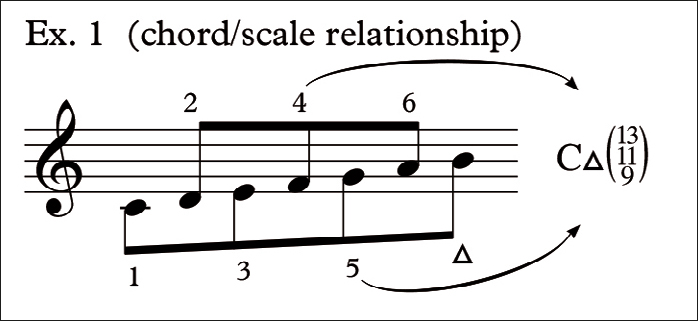

With a basic understanding of these four-note chord symbols, we should be ready to add more notes if required, to create more colour in our harmony. These added notes are invariably numbered above 7 and continue the 'ladder of odd numbers' that we have in our basic chord symbol. They can reach all the way up to 13 and are known as 'extensions'. We can see in Ex.1 how a scale can be reorganised into an arpeggio – this is known as the 'chord/scale relationship'. This is a useful concept if you want to begin improvising.

Extensions

Chord symbols denoting these more colourful chords can seem complex. But things are made simpler by the fact that any of the ‘extension' numbers added above 7 in a symbol imply that the 7th is there already. Chord symbols G9, G13, Gm9, Gm11 etc. have at least the 3rd and 7th in the chord and maybe one of the other colour' notes as well – but these do not have to be included in the written chord symbol. They are understood to be there.

If, however, any of these extension notes were to be raised or lowered by a semitone – as we were able to do with the 3rd, 5th and 7th – then the 7th (or 6th or Δ) would need to be stated as a reminder, a precaution. Hence, we use G7b9, GΔ#11, Gm7b13, G7+#9, etc.

If the chord symbol we are faced with has none of these extensions included, then we are, of course, free to add them. Remember, a chord symbol is not notation – it is not telling us all the possible notes we can play and it is certainly not telling us how to ‘voice' (space) the notes in the chord. We have to figure these points out for ourselves.

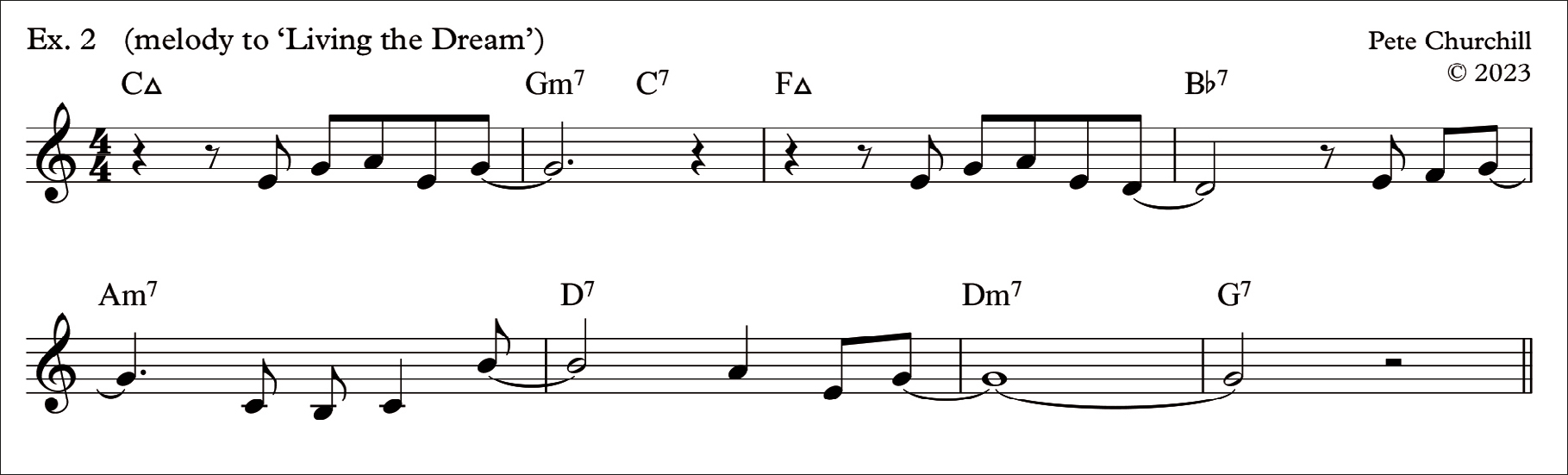

Ex. 2 is a simple 8-bar melody (called ‘Living the Dream') – as might be found at the start of any lead-sheet of a jazz standard – harmonised with basic seventh chords (without extensions):

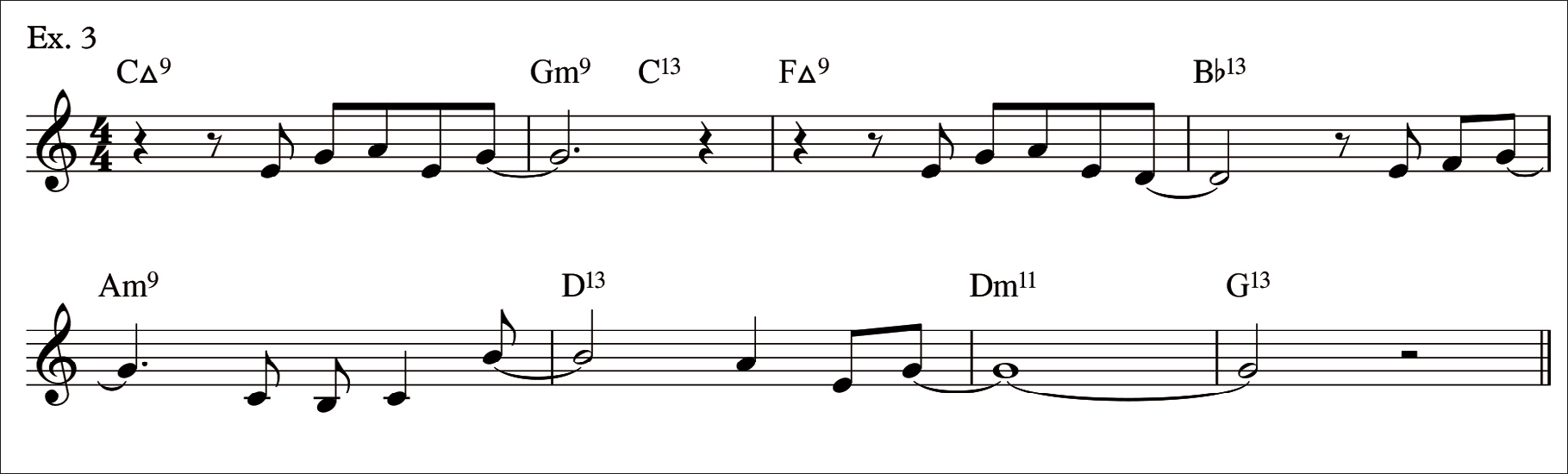

It is usually safe to add 9ths to m7 and Δ chords, and a general rule of thumb is that if we are harmonising a diatonic melody (and most American Songbook melodies are diatonic), any extensions we add are chosen to reinforce the key centre, thereby supporting the melody. In Ex. 3 we see the chords expanded to include numbers above 7 – many of them implied by the melody.

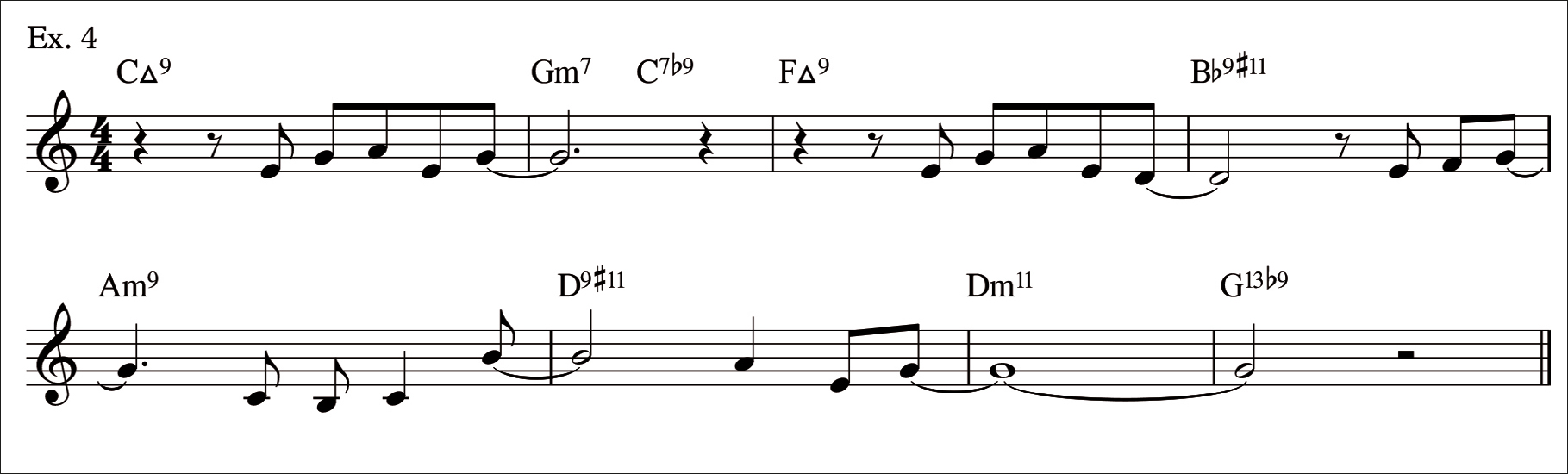

Chromaticised extensions can provide interesting variations in harmony; but these should be added with care and not conflict with the melody. Ex. 4 provides an example of this, ensuring that melody notes are preserved.

In order to get started, we need to divide the notes of a chord into two areas: notes providing essential harmonic information and those that can add colour or tension – our 'extensions'.

Voicing 3rds and 7ths

The simplest way to voice a chord is to use the root, 3rd and 7th. Good voice-leading through a progression is achieved by moving the harmony notes to the nearest 3rd or 7th of the next chord.

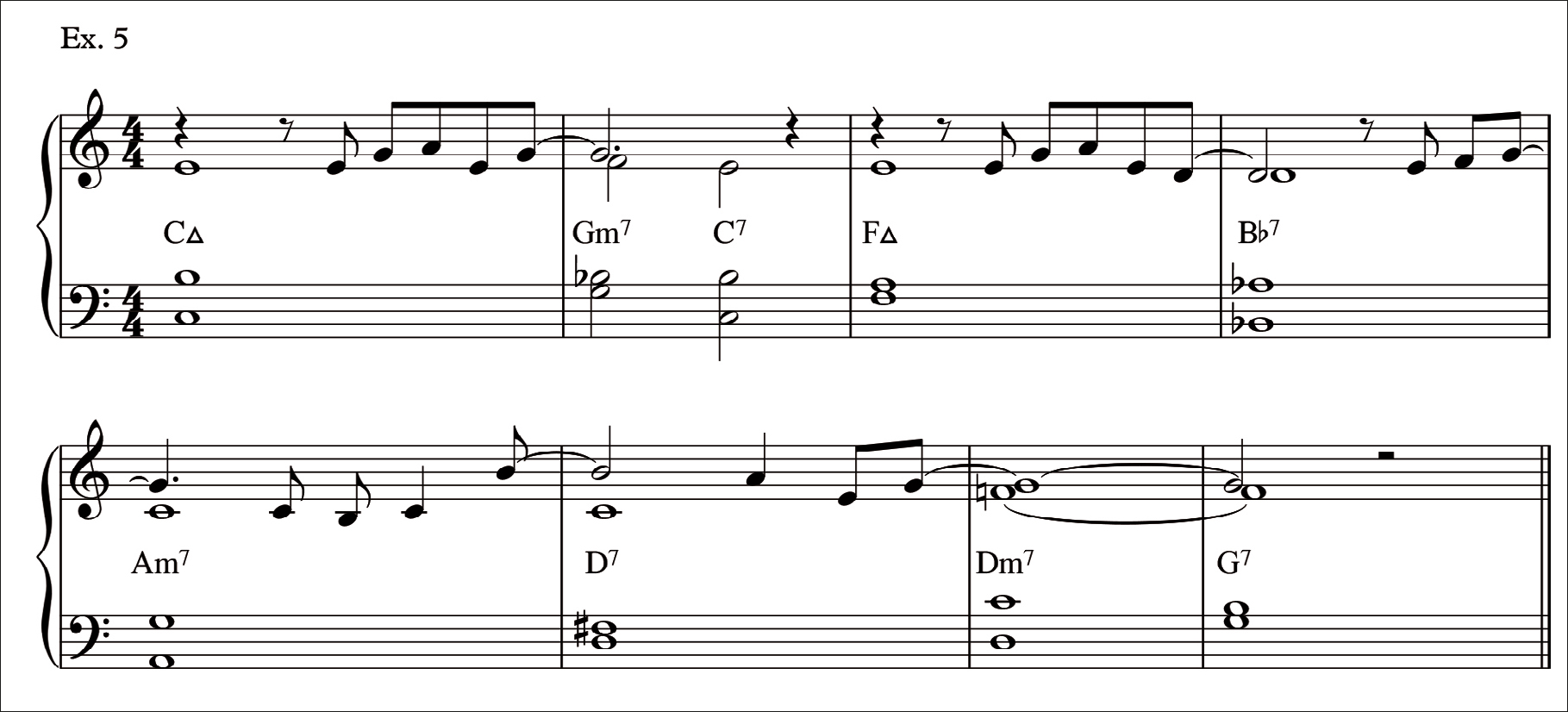

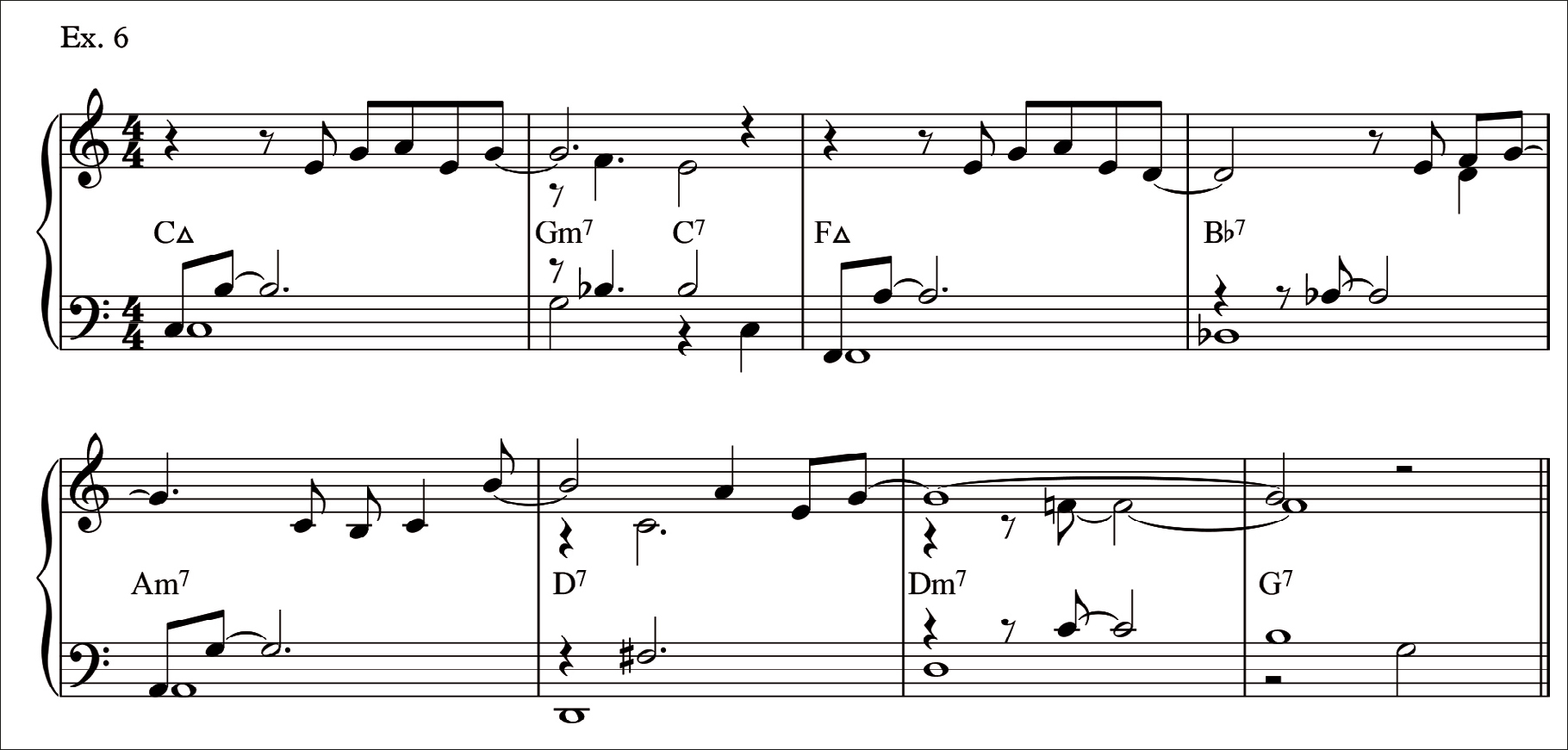

In Exx. 5 and 6 our melody occurs with just the essential notes voiced beneath. Notice how the notes are distributed so as to give a sense of three layers: bass, melody and a middle layer of harmony that has a separate rhythmic identity from the melody.

We can see from these last examples that the left hand is playing either a root and 3rd or a root and 7th, and that the right hand is playing the melody with the remaining 3rd or 7th – providing the melody isn't covering that note already.

Open voicings

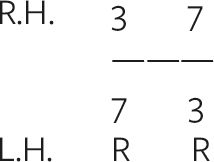

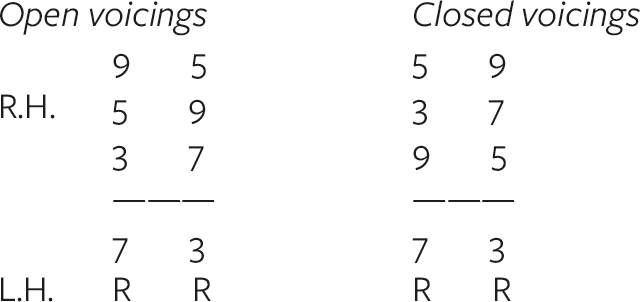

We can now build a template for an ‘open voicing' using these root, 3rd and 7th voicings as a foundation. Note how here the 3rd and 7th are played by the thumbs and that the 3rd could be a m3, 3 or sus4 – and, similarly, how 7 could mean 6, 7 or Δ.

Voicing the extensions

If I wish to add two extensions to my voicings – e.g. a 9th (b9 or #9) and then one other from the colours around the 5th (11 or 13) – and still maintain the melody, then I must adjust my template depending on the register of the melody. When the melody is high, my voicing can be open; but when it is low, I must collapse my open voicing to a closed one. The template now looks like these:

Remember: 9 = b9, 9, #9 and 5 = 11, #11(b5), 5, b13(#5), 13

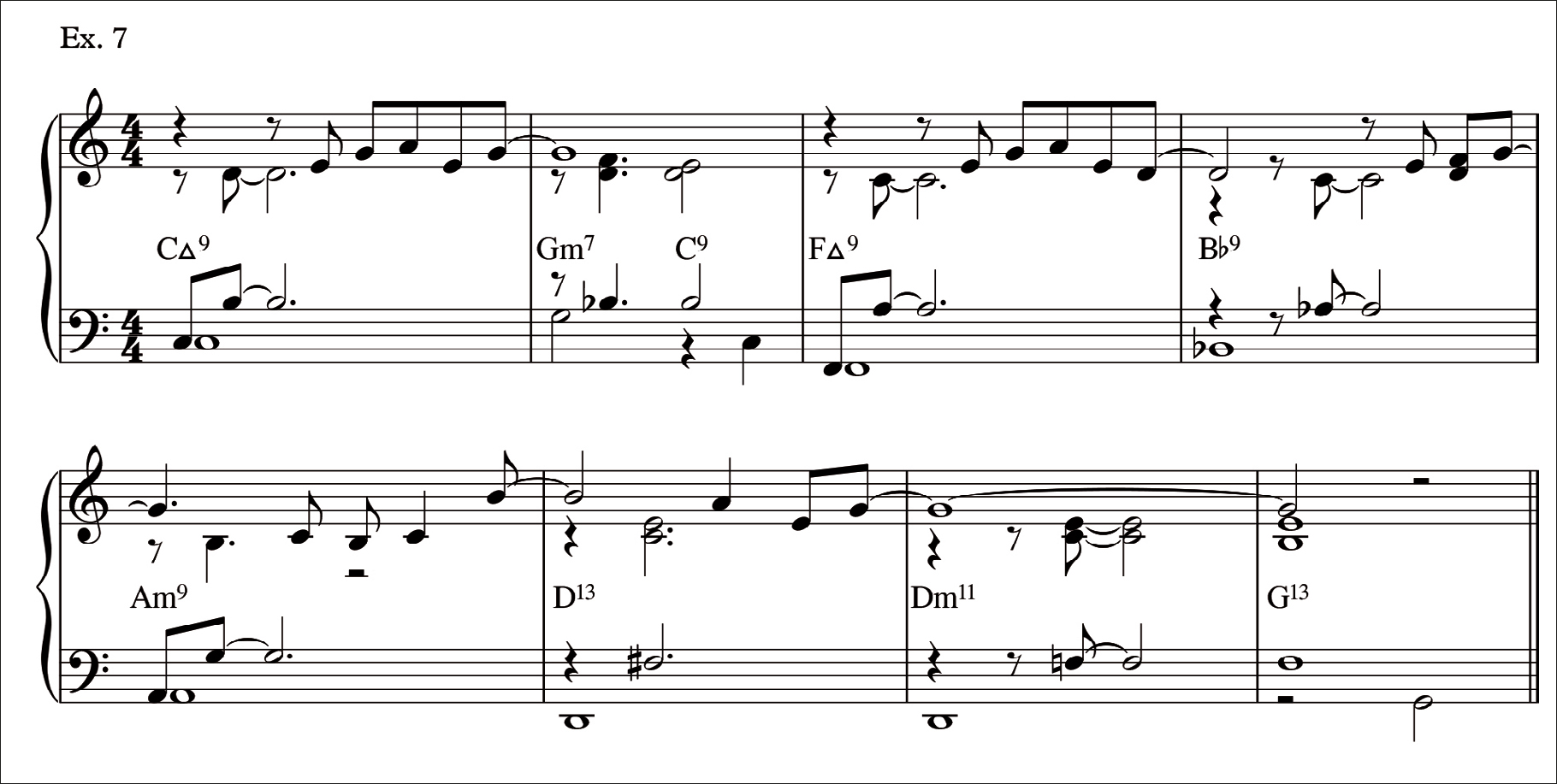

These templates are reflected in Ex. 7:

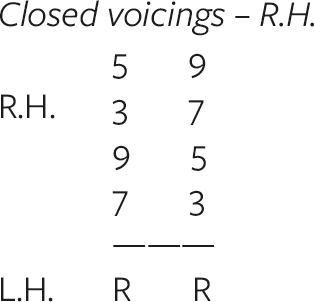

Finally, if you are accompanying someone singing or playing the melody and simply wish to voice the chords independently, then it makes sense to play the bass notes exclusively in the left hand and voice the rest of the chord – the other four notes of your template – in closed position in the right hand. Here's a revised template for this format:

And a realisation in score form (Ex.8):

There, the whistle-stop tour! If you grasp these basics, the rewards will be manyfold.