Contemporary classical composer Angela Slater did her grade exams, then a music degree and was working on her PhD in composition when she had a revelation. ‘It horrified me to realise that I hadn't noticed that I hadn't been introduced to women composers,’ she tells me.

This was a turning point in Slater's life and career. She began to research historical and contemporary female composers, and in 2017 founded Illuminate, a project to promote the work of emerging women composers and performers alongside historical repertoire by women. She also began to reflect on her own music education. ‘For a music person I'm from quite a modest background – I went to a state school. I had instrumental lessons, and all through the grade exams, all through GCSE and A level, and even when I got to university, there were no female composers.’

Representation on syllabuses

She realised that the repertoire set for grade exams is hugely influential. ‘It's one of the things that's consistent throughout my musical education. I feel like that's probably true of a lot of musicians, both amateur and professional – the influence on what we come to understand as the history of music and therefore what repertoire is important’.

Slater wanted to establish the facts. She went through every ABRSM piano syllabus from 1999 to 2020, from Grade 1 to Grade 8, checking how many pieces there were in total and how many of them were by women. The results were stark. From 1999 to 2020, there were 1,737 pieces in total. Only 77 were by female composers. That's just under four-and-a-half percent. Even in the 2011-12 syllabus, which had the highest number of pieces by women, it was only seven percent. Slater also recorded which pieces were included in the grade books and which were on the syllabus but not in the books. She also looked at which list (A, B or C) the pieces by women were featured on.

‘It's not just the general representation overall – which is extremely low – but then you look at access,’ she says. ‘If people don't have the financial means to buy tons of other books then you're creating another barrier – they can't engage with music by women. List A in the main exam books doesn't have any women composers for a good decade.’

Slater released her research in December 2019; it's the basis of a book chapter, ‘Invisible Canons – Towards a Personal Canon of Female Composers’, to be published by Routledge later this year.

Penny Milsom, ABRSM's executive director for products and services, spoke to the Sunday Times when it reported on Slater's findings. She said: ‘We are committed to increasing gender diversity as part of our approach to refreshing our syllabuses and publications. We support other colleagues across the music industry working to increase the representation of women in music.’

Barriers to engagement

I ask Slater about barriers to engagement with music by women and the difficulties faced by female composers themselves. ‘I've heard the argument for not playing women composers because it won't get you well known as a pianist,’ she said. ‘I've also heard it regarding conductors – it's not the repertoire that conductors need to know to get good positions. But if you keep continuing that it's a self-fulfilling prophecy. Things will never change.’

There are also many practical issues. ‘I run an orchestra – I can't be a hypocrite, so I have a 50-50 programming policy. Sometimes it's really difficult – perhaps we don't have money, or we don't have this or that instrument. It's hard to actually find the music out there, or if you do find it, then there's the financial barrier of really high hiring prices.’

I imagine Slater's male counterpart, busy composing and trying to get commissions, while she takes on this extra burden. ‘Yes, it's exhausting! Male composers can just be composers, but women have to be advocates as well for themselves and others.’

For women writing music now, just as in any other profession, the majority will have to negotiate dealing with caring responsibilities – children or elderly parents – while their male counterparts will not. Composer Emily Doolittle, in her article ‘Composing and Motherhood’, lays out the problems: ‘Finding enough time to compose while earning enough to pay for childcare – in such an underpaid field as composition – is impossible for many, and grants seldom come with funding for childcare.’

Doolittle's suggested solutions include abolishing upper age limits on both grants and competitions for composers. ‘The focus on young composers comes with an attendant assumption that if someone hasn't “made it” by 35, they never will (despite the existence of such well-regarded late-blooming composers as Rameau, Scarlatti, Janáček and Scelsi). Women who have kids in their late 20s or early 30s may miss out on the key years for participating in young composer programmes, only to find that just as the kids are old enough for them to participate more fully, they are excluded on the basis of age.’

Lost female composers

What about female composers of the past? Often, we read about ‘lost’ or ‘rediscovered’ female composers, and it turns out they were far from obscure when they were alive. Indeed, many were celebrated in their lifetimes. How and why do they get ‘lost’?

‘I find this quite distressing,’ Slater says. ‘They're often well respected by their male counterparts, their works are played – there's also a sexism within musicological research. The male composers have always been the ones that have had books and endless editions created of their works. If a whole body of female composers’ works are still in manuscript form or blocked by really high hiring prices, if there isn't even a way of hearing the music – there's tons of it that's not recorded – then that creates barrier after barrier.’

French composer Elisabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre (1665-1729) was described by one contemporary critic as ‘the marvel of our century’. Like Lully and Rameau, whose lifespans bookended hers, she wrote large-scale works – she was the first woman to have an opera performed. But she disappeared until rediscovery in the 20th and 21st centuries, while Lully and Rameau were never forgotten.

Many historical female composers were directly prevented from working by the men in their lives. ‘Clara Schumann was encouraged to essentially stop composing by Robert. Then there's Amy Beach,’ says Slater. ‘When she wanted proper composition lessons, her husband said, “Oh no, it will spoil your natural composing talent.”’

Nineteenth-century Brazilian composer Chiqinha Gonzaga's husband forbade her to compose. She divorced him and was declared ‘dead and of unpronounceable name’ by her father. Later, she was so successful as a composer that she faced another problem – people using her music without paying her. So she set up the first copyright society in Brazil.

This is why Slater has no truck with those who argue that ‘cream will rise to the top’ regardless. ‘It's ignoring the historical and social structural suppression of women and women composers.’

American composer Katherine Hoover, who died in 2018 at the age of 80, described her experience as a student at the Eastman School of Music in the 1950s. ‘I was the only female in class, with six guys, all grad students. I was an undergrad, and I just sat there, and they never bothered to look at my work, and that's the way it was.’

Keeping up the pressure

Why does Slater think the pace of change is so slow? ‘Nicola LeFanu, who's a couple of generations above me, told me that the pendulum swings, but then it swings back the other way. She told me in the 1970s that there was a women composers’ society that had been set up for this very reason.’

The society had been in existence for some years when the members decided to close it. ‘They somehow naively thought, oh well, we've sorted that. Then [LeFanu] noticed that as a composition lecturer at York Uni that she was getting fewer opportunities. So were her female colleagues, and her students were getting even less. She thought it was curious that things seemed to have slumped back. If you don't keep your eye on the ball the patriarchy very quickly re-establishes itself.’

While men get to ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’, women must keep rebuilding the work of previous generations. ‘[LeFanu] said to me, “With your Illuminate project, what you must do is just keep going, once you think it's fixed.”’

Slater's ambition for Illuminate, which she runs with two other female composers, is to ‘infiltrate the canon’. ‘We have different performers-in-residence each season, and we commission five or six new works by women composers that are working today, programmed alongside historical works by women composers. We create a dialogue across history and demonstrate there is a lineage from the past.’

An Illuminate concert in 2018

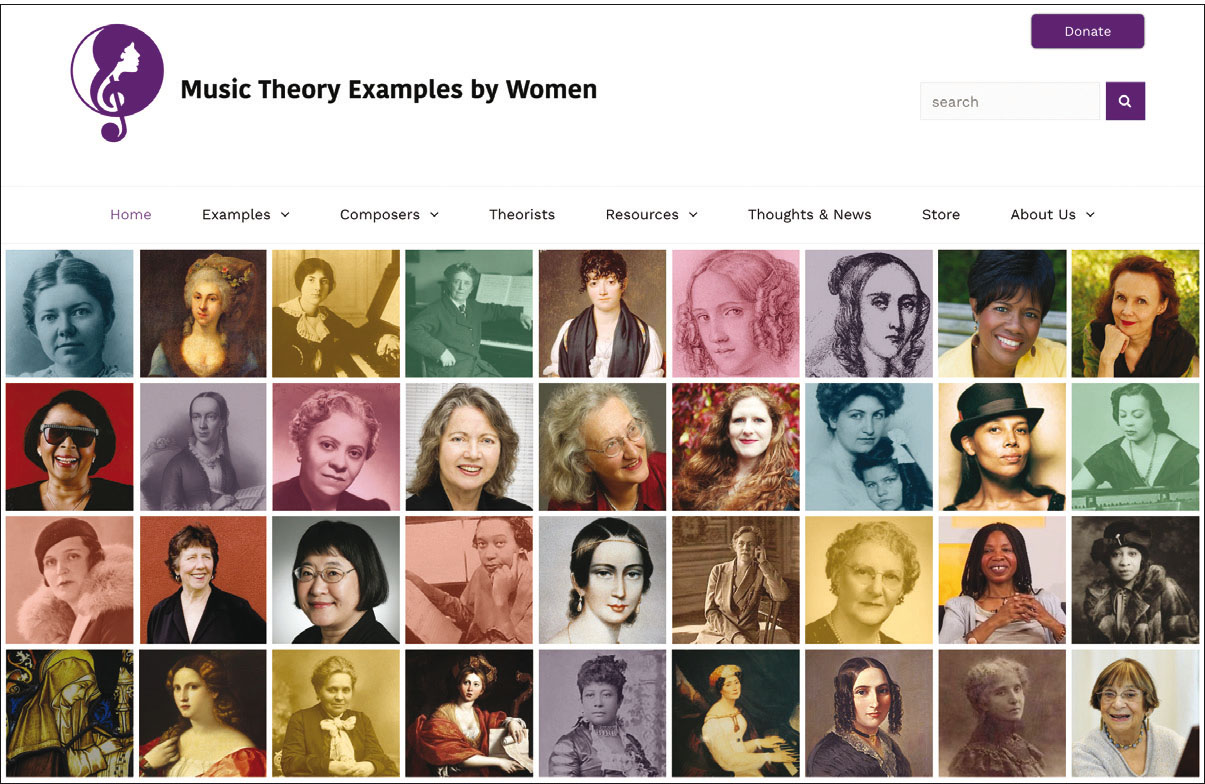

Music Theory Examples by Women

Slater and her team make sure their decisions have practical and lasting effects. ‘My idea was to have different performers each time – essentially to influence and affect the repertoire that they have themselves. When they have left Illuminate, they may then play and programme some of these pieces again, and more and more audiences will hear this music.’

How teachers can help

I ask Slater how we as music educators can promote work by women. ‘I know music education is always time pressured, so it's a difficult thing to ask’, she says, ‘but there are sources out there. There's a website called Music Theory Examples by Women [https://musictheoryexamplesbywomen.com], so if you're teaching music theory, instead of using the default examples from male composers, you can use one from a female composer.’

I ask Slater if there are any resources for younger children. ‘No! It's a huge gap in the market’.

Returning to her own music education, she tells me what she wished her younger self had experienced. ‘A normalisation of women composers – here's Beethoven but here's Emilie Mayer, here's Debussy but here's Louise Farrenc, here's Schumann but here's Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn. They're just names that roll off the tongue like those of the male composers.’

Find out more about Illuminate at www.illuminatewomensmusic.co.uk