The Model Music Curriculum (MMC) was released by the Department for Education (DfE) in March. Its reception from the teaching community has been mixed, but one of the recognised positives is its emphasis on using a broad range of repertoire in our teaching – the authors include lists of repertoire from a variety of styles and genres, from medieval times to present day. Like schools minister Nick Gibb, who wrote the foreword, I first heard Allegri's Miserere at school; luckily, I also heard David Fanshawe's African Sanctus, which features Fanshawe's field recordings from Africa. I loved both pieces, and I'm sure they equally inspired my love of music and led to my career as a musician, in which I've played in styles from classical to Bollywood.

Categorically clear?

The MMC is aimed at specialist music teachers and non-specialists at Key Stage 2, but contains what could be seen as a bewildering list of ‘traditional’ repertoire, some of which is presented in a confusing way. Appendix 2 (p.61) contains separate lists, starting with Western classical music classified by period: Early, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical and Romantic, followed by the 20th and 21st centuries and Musical Traditions. For the latter, the MMC suggests that ‘it makes sense for there to be some exploration of how the music sits within the culture of the country’, and that ‘it is important to recognise that modern British identity is rich and diverse, resulting in communities which celebrate and explore their own specific, localised “cultural capital”’ (p.9).

I feel that good intentions are expressed here, but beware of some of the terminology. Categorising music can imply value judgements – the list starts with Western classical music, symbolically placing this genre first and foremost, giving it prestige. Of course, lists have to start somewhere, and children should be aware of Western classical music (I'm not from a musical family – I first heard classical music at school), but intrinsically, it holds no more value than, say, the Beatles or Indian classical music. The ‘Stormzy vs Mozart’ debate encapsulates this thorny issue. (See tinyurl.com/b6r48bxc).

Musical Traditions Foundation listening, Key Stages 1 and 2, p.10 © MMC, Department for Education

But why?

The sheer length of the Traditions list may leave you wondering where to start. Might you go straight to something you've vaguely heard of – a sea shanty for instance, or perhaps start at the beginning and work your way through? After being quite prescriptive about what we should listen to, there is little explanation for the choices that follow. There are no reasons why the music has been recommended, no links to specific versions and, apart from the Foundation listening, no background information.

There is a danger here of ‘othering’; this music doesn't ‘fit’ with Western music, it is foreign, something we may not understand, requiring a separate list. On closer inspection, the 21st century list contains a Portuguese Eurovision Song Contest winner, Amar pelos dois, a Bollywood film song, Aankh Marey, and a piece by Malian superstar kora player, Toumani Diabaté. Shouldn't these pieces be on the Traditions list? The problem here lies with trying to define music when there is so much that defies categorisation.

The MMC suggests that Traditional, Folk and World music are especially useful in ‘developing aural awareness' – this is another instance of ‘othering’. Yes, often non-Western music is learnt aurally, but any music can be learned and played by ear, without the need for staff notation. The problematic term, ‘World music’, has crept into the document three times (pages 60, 61 and 78). The Guardian declared the term ‘dead’ in 2019; with echoes of empire, it is an uneasy label used to cover a massive area of music with the only thing in common being its non-Western-ness. In fact, the phrase is a marketing term, invented in the 1980s as a way of categorising music in record shops. The glossary defines a world music ensemble as ‘a group…playing instruments traditional to a country, continent or culture’. This is therefore an odd inclusion – surely this describes any ensemble, anywhere in the world, including an orchestra?

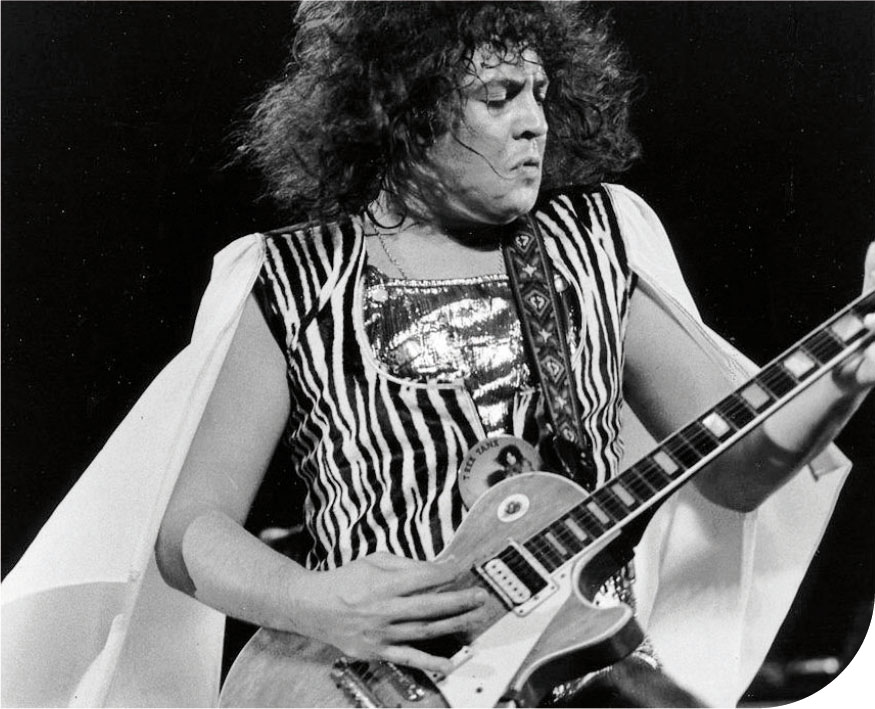

The music recommended in the MMC is wide-ranging. The 20th century list spans Rachmaninov, Elvis Presley, Daft Punk, and Thomas Adès; similarly, the 21st century repertoire covers Stockhausen, T. Rex, Hans Zimmer and George Ezra. Hang on – surely some mistake. Marc Bolan (T. Rex) died in 1977…

In making a YouTube playlist of the Musical Traditions pieces for Key Stages 1 and 2 (p.71), my in-depth look has thrown up more anomalies and mistakes that need clarification to ensure teaching is accurate. In Appendix 3 (p.74), some context is given for the Foundation pieces for KS1 and 2, but I find it odd that Chopin's mazurka is listed as folk – the explanation itself defies that categorisation. For Polish folk music I would suggest listening to, say, the Warsaw Village Band, not a piece by a Western classical composer. The YouTube playlist I made can be found at tinyurl.com/9nx76jx7.

Marc Bolan, leader of T. Rex, in concert in 1973

The two versions of Wassail on my playlist are very different; it is a folk song, but Vaughan Williams has turned it into something that sits in the Western classical canon. Which one would you choose, and what ‘cultural capital’ might you unconsciously attach to each version? This will depend on your own background and preferences – and how much time you have to find and compare examples!

Clearing up a few things

Mistakes add to possible confusion with unfamiliar repertoire and can be off-putting if music can't be found due to spelling or factual errors. Here are some rectifications from the KS1 and 2 list:

Year 1

- ‘Mo Matchi’ (Song of the Bees) should be Moumachi Moumachi.

- ‘My Shoes Are Made of Spanish Leather’ should be Boots of Spanish Leather. The song also isn't English – it is written by Bob Dylan.

Year 2

- Mylecharaine's March is Manx, not Irish.

- ‘The Old Woman Wrapped Up in a Blanket’ should be There Was An Old Woman Tossed Up in a Blanket.

Year 3

- ‘Now charia de’ (A Boatman's Song) should be Nao Chariya De Pal Uraiya De.

- Drummer's Reel – The Dhol Foundation are not from Pakistan; they are UK Punjabi/Sikh.

Year 4

- ‘Namuma’ should be Nanuma.

There are mistakes in the Key Stage 3 list too; with my rudimentary Spanish I spot straight away that ‘Ojios Begros' from Mexico is unlikely; in fact, it is Ojitos Negros. There isn't a song called ‘Fado’ by Amália Rodrigues (a Year 8 Foundation piece); Fado is a whole genre of music, not a song title. These mistakes are clumsy and culturally insensitive and should have been checked before publication; it is well-known that other mistakes have been corrected since publication without acknowledgement.

Rather than separate lists, perhaps all music since the 20th century could have been listed chronologically, or alphabetically. The history and development of music has crossed over so much since then – without the transatlantic slave trade and the influence of African music in the USA we wouldn't have jazz or the blues and therefore no rock and roll, soul, funk or disco.

African Sanctus doesn't feature in the MMC, but if it did, how would it be classified? It is a choral mass, so should it be on the same list as Allegri's Miserere? It isn't ‘traditional’, or ‘classical’, it has elements of both, but there-in lies the problem with lists and categories.

There is some fantastic music recommended in the MMC, but avoid making comparisons between genres, styles and eras – we should be modelling listening to the music for its own sake. Music is music and it all should be given equal value. Ultimately, dip in and find something new to enjoy!

How can you deliver authentic musical experiences in your classroom based on this wide-ranging repertoire? Non-specialists may struggle to turn the MMC into a ‘living, vibrant reality in the classroom’ (ISM), and the MMC itself states that supporting resources and opportunities for CPD will be created by numerous partners' (p.6). Working with external providers can bring expertise in unfamiliar music – search for musicians or workshoppers in your area, or ask parents.

Further information

The Rough Guide to World Music (Penguin Books)

Songlines (www.songlines.co.uk)

Jazzwise (www.jazzwise.com)

The English Folk Dance and Song Society (www.efdss.org)

The MMC can be read in full at www.gov.uk/government/publications/teaching-music-in-schools