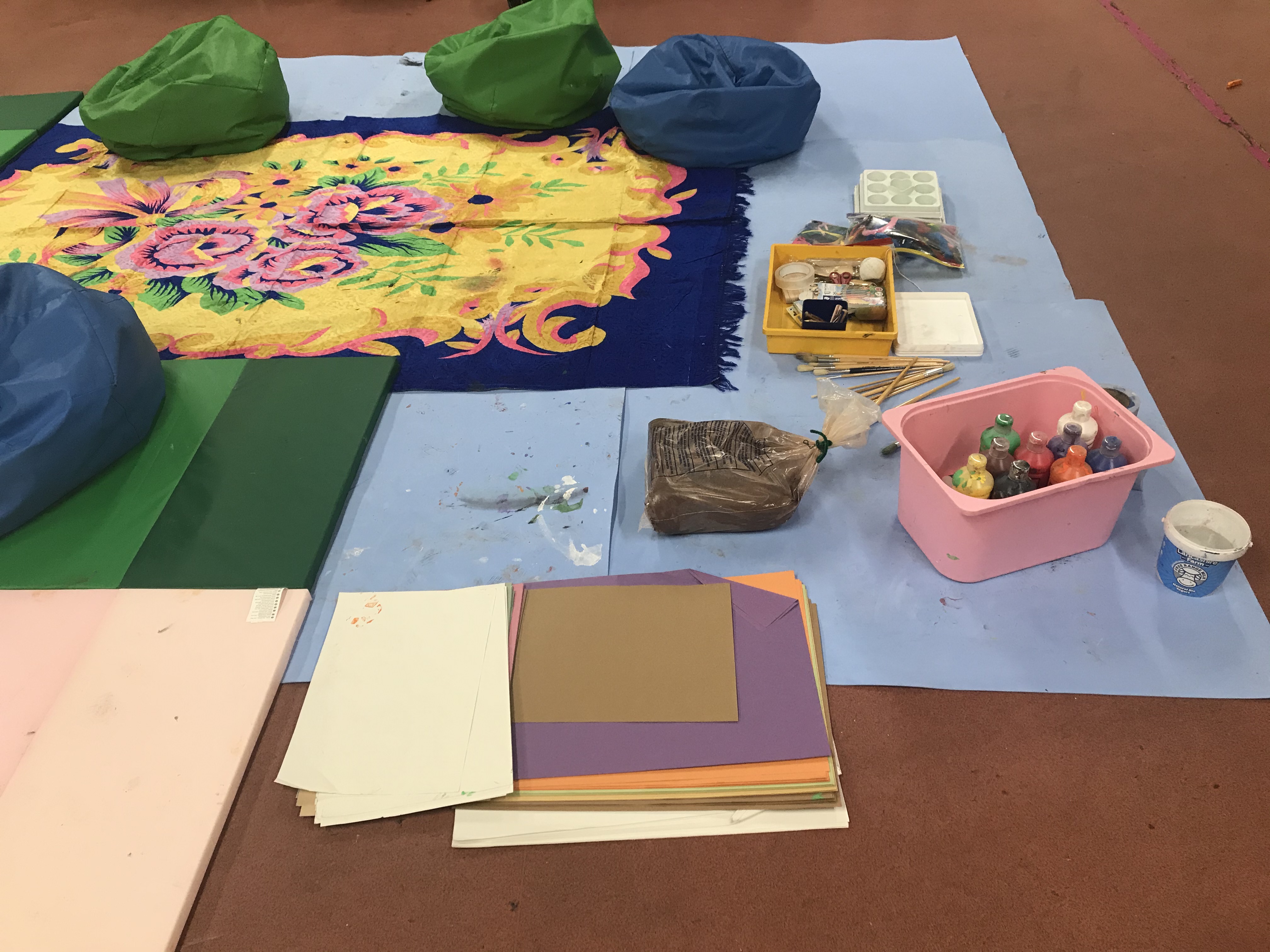

In response to the Grenfell Tower fire, art therapist Susan Rudnik founded Latimer Community Art Therapy (LCAT) in June 2017. Four years on, the Painting Together Group for parents with their babies and young children remains. Facilitated by art therapist Dean Reddick and Ros Taylor, the group is part of the larger ongoing therapeutic intervention for adults and young children in the local community.

LCAT’s work, including the Painting Together group, is a fine example of responding inventively to the unique needs of a community.

Background to LCAT and the Painting Together group

Susan Rudnik has lived in the community for more than two decades. Susan set up the first art therapy space just three days after the fire. Several more soon followed.In her paper, Out of the Darkness: A Community led Art Psychotherapy Response to the Grenfell Tower Fire, Susan describes the organisation of the work and the therapists as, ‘giving a sense of control in the midst of the chaos’.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting Nursery World and making use of our archive of more than 35,000 expert features, subject guides, case studies and policy updates. Why not register today and enjoy the following great benefits:

What's included

-

Free access to 4 subscriber-only articles per month

-

Unlimited access to news and opinion

-

Email newsletter providing activity ideas, best practice and breaking news

Already have an account? Sign in here