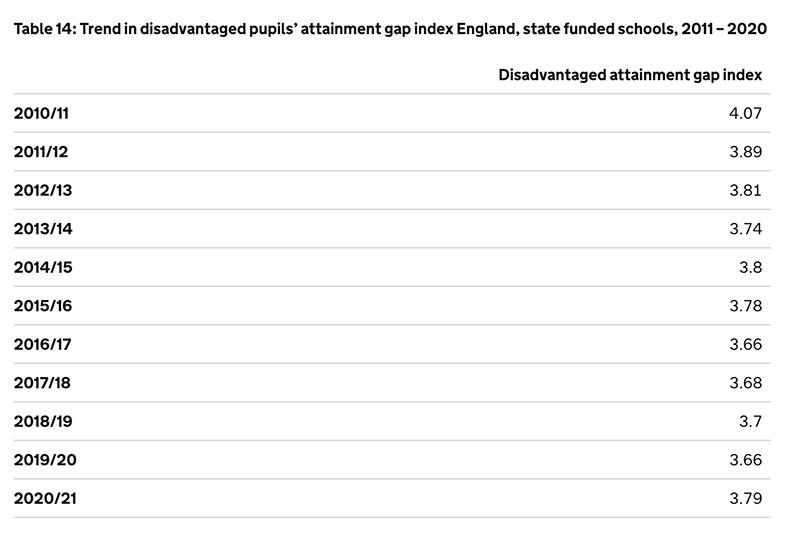

The latest key stage 4 performance statistics show that the disadvantage gap – the relative attainment between disadvantaged pupils and all other pupils – has widened to 3.79 in 2021.

This compares with a gap of 3.66 points in 2019/20 and 3.7 in 2018/19 (DfE, 2021).

The so-called disadvantage gap index summarises the relative attainment gap based on average grades in English and maths GCSEs between disadvantaged pupils and all other pupils. It ranks all pupils in state-funded schools in England and asks whether disadvantaged pupils typically rank lower than non-disadvantaged pupils. A gap of zero would indicate that poorer pupils perform just as well as pupils from non-disadvantaged backgrounds.

Pupils are defined as disadvantaged if they are known to have been eligible for free school meals at any point in the past six years (from year 6 to year 11), if they are recorded as having been looked after for at least one day, or if they are recorded as having been adopted from care. The latest DfE figures show that in 2021 26.4 per cent of pupils at the end of key stage 4 are recorded as disadvantaged. This compares with 26 per cent in 2019/20 and 26.5 per cent of pupils in 2018/19.

The DfE’s report states: “The widening of the disadvantaged gap index may reflect the difficult circumstances that many pupils will have experienced over the last academic year which saw various restrictions put in place in response to the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g. periods of lockdowns and tiers) that resulted in restricted attendance to schools and periods of home learning.”

A widening gap: The trends over time show progress since 2020 in closing the disadvantaged attainment gap index, although Covid has caused a return to 2015/16 levels (Source: DfE, 2021)

In the recent Spending Review, the government pledged to invest an extra £4.7bn into the core schools’ budget by 2024/25. This is “over and above” the 2019 settlement for schools, which covered the period until 2022/23.

There was also an additional £1.8bn for Covid-19 education recovery, bringing the government’s total spending for education recovery to £4.9bn.

This includes a £1bn recovery premium for the next two academic years to help schools to deliver evidence-based approaches to support the most disadvantaged pupils. It also includes £324m in 2024/25 for additional learning hours for 16 to 19-year-olds.

Critics were quick to point out that the £4.9bn is nowhere near what the government’s former education recovery tsar Sir Kevan Collins had said was needed before he quit the role in protest.

The Association of School and College Leaders said the latest figures on the attainment gap “reinforce the need for more government investment in education recovery”.

General secretary Geoff Barton added: “It is clear that disadvantaged young people have been particularly badly affected by the pandemic and the associated disruption to education which has resulted not only in periods of lockdown but large numbers of students having to periodically self-isolate even when schools are fully open.

“While we welcome the funding that the government has committed to education recovery, we are far from convinced that this is sufficient to address the educational damage caused by the pandemic, particularly to young people in persistent poverty. The fact that the disadvantage gap has widened should serve as a call for further action.”

Elsewhere, the latest key stage 4 figures – from the summer 2021 GCSEs, which were awarded using teacher assessed grades due to the impact of the pandemic – show that of the 575,863 year 11 students 51.9 per cent achieved a Grade 5 or better in English and maths. The average Attainment 8 score of all pupils was 50.9.

- DfE: Academic Year 2020/21: Key stage 4 performance, November 2021: https://bit.ly/3n2tJdA