Defending tutor books

I feel I must take issue with Georgina Murphy Clifford's many negative comments about recorder tutor books, her idea that using a tutor book limits a teacher, and her assertion that children should be encouraged to play only tunes they already know (‘Beyond the tutor book’, Music Teacher, February 2020.)

Surely part of the purpose of education is to introduce children to new things and to expand their horizons beyond the things they already know. Different tutor books suit different teachers and different teaching situations, but I have used John Pitts’ excellent Recorder from the Beginning series successfully for many years. Unlike the anonymous tutor books Georgina describes, these contain a mixture of well-known children's songs, traditional tunes, classical music and specially composed music.

I see these books as a starting point for my teaching, not the be all and end all. My groups don't learn all the tunes and exercises from the books; they do lots of extra things that aren't in the books, and I take responsibility for teaching recorder technique which, as with any instrument, can't really be learned just from a book.

Using a tutor book doesn't preclude children from trying to play any pieces of their own choice. Most youngsters love music of all kinds if they are introduced to it sensitively and given suitable challenges. Simply assuming that they won't be interested does them an injustice.

Jean Murray, director, Edinburgh Young Musicians

Georgina Murphy Clifford responds:

It has been a pleasure to receive feedback on the article ‘Beyond the Tutor Book’. It has been suggested that taking inspiration from informal learning is centred around the choice of repertoire. In my article I explained Keith Swanwick's view: music lessons should reflect life ‘outside of the classroom.’ I continued: ‘undoubtedly repertoire is not the only thing that could link to children's daily lives’.

In initial lessons when children are having their first experience of learning the recorder, I have looked towards pupil choice and ‘real world’ musical examples. In broader education, the philosophies of Dewey, Piaget and Montessori (et al) all start with ‘what does the child already know’ and use this as a basis for curriculum planning. The National Curriculum follows similar sequencing, using a constructionist model of pedagogy by starting with what the child knows and building on pre-existing experiences to acquire new knowledge. For many of the children I teach we start with repertoire as the known, using this to acquire new knowledge in musical literacy and instrumental technique.

I found myself patronising children by asking them to play ‘Buzzy Bee’ on the recorder when they could be learning from real-world experiences by playing along to Ariana Grande (as one example). This is not a new theory, merely a reworking of well-established pedagogies such as Kodñly and Dalcroze. In previous generations children were exposed to a similar homogeneity of folk music, but this is no longer the case in our multicultural society. A teacher cannot assume what is (as Ms Murray describes) ‘well known’. Opening a dialogue with students and working together to acquire new knowledge provides a flexible scaffold to learning, as advocated by Vygotksy. In some cases I have learnt just as much as my pupils.

It is important to show that the recorder lives outside the classroom. As larger selections of society exist in rural or urban isolation, families are finding it more difficult to transport their children to after-school ensembles or concert opportunities. Pressures on curriculum time within our exam-dominated educational society are squeezing in-school opportunities for ensemble making. Streaming services and online resources are invaluable – as Ms Murray quite rightly describes – in introducing ‘children to new things and to expand their horizons beyond the things they already know’.

I doubt any of us rely on one source for our curriculum material, and there are as many different approaches to pedagogy as recorder students in the world. Not all recorder teachers are specialists: only 56 percent of teachers responding to a survey said that they identified the recorder as their first study instrument, and only 29 percent had a tertiary level qualification in music. Focus group discussions with specialist recorder teachers show large discrepancies between technique advice set out in tutor books and their beliefs about technique as recorder professionals.

For less experienced recorder teachers, often working in self-employed isolation due to cuts to local authority music services, we might ask: where do they find their technique advice? For the parents of children learning in school without regular contact with a recorder teacher: where do they find their technique advice? I have no firm evidence, but I would suggest that is unlikely to be Walter van Hauwe, and more likely their child's tutor book.

The tutor book, as proven by academic research, remains hugely popular in its largely undeveloped form since the baroque period. Pedagogical development is vital in producing happy recorder players and teachers of the future. Opening up pedagogical debate between teachers should be welcomed and encouraged. Using the words of Ms Murray: ‘simply assuming that [teachers] won't be interested in’ experimenting with new pedagogical ideas ‘does them an injustice’.

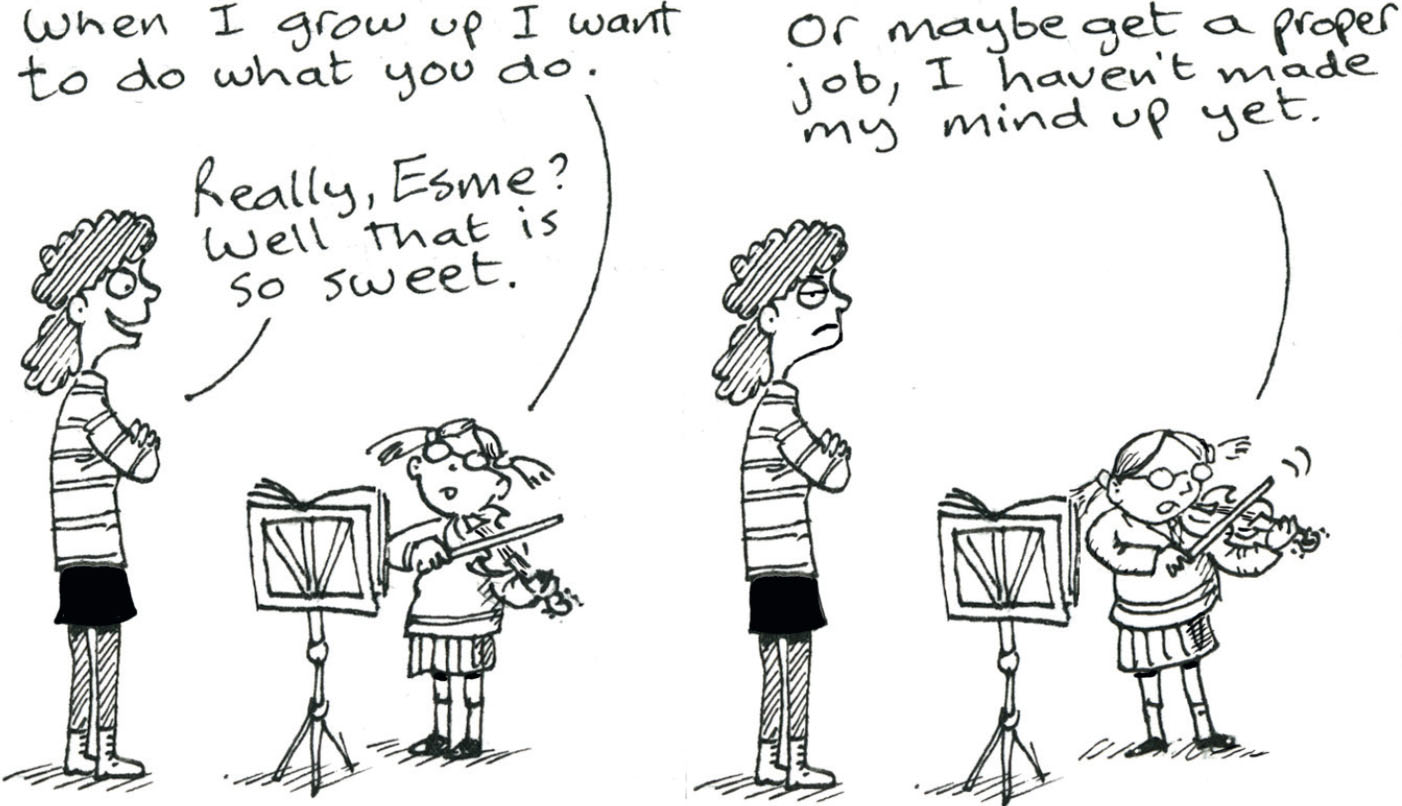

The Peris by Harry Venning