Star letter: Diverse species

In ‘Species under threat’ (MT December 2021, p.35), Claire Jackson aptly compares endangered musical instruments with animals heading for extinction, such as rhinos and tigers. These iconic creatures need protecting. However, the survival of microscopic algae and plankton is equally as important: survival of the largest depends on survival of the smallest.

As we consider the endangered ‘oboe, French horn, euphonium, viola, bassoon and double bass’, perhaps we should review attitudes towards the humble ocarina at the start of the ‘orchestral food chain’. The ocarina is also endangered because orchestrally minded teachers rarely consider ocarina playing as a serious option. Yet mastering the ocarina can be key to survival of its ‘more important’ larger siblings.

My daughter played the ocarina from the age of three onwards, and started the French horn at 15, progressing to Grade 8 Distinction in under three years. This remarkable achievement owes much to playing the ocarina, and also piano, from an early age. She is now completing her M.Mus. performance degree and starting out in an orchestral horn career.

I mention my daughter because I have seen her musical journey first-hand. Others have progressed similarly: one family offered string lessons to their girls on the proviso that they mastered the ocarina first. All three played ocarinas eagerly from the age of five onwards, went on to study violin and cello at the Royal Academy of Music, and are now successful soloists.

Peripatetic teachers in Scotland have reported that primary school ocarina players have disproportionately taken up orchestral instruments in secondary school. Why? There are many answers. One is that learning the ocarina produces quick musical results, motivating pupils to want to carry on making music, rather than to give up. Another is that ocarina playing develops a critical ear for intonation, fundamental for playing any instrument.

In my experience, the ‘unwieldy’ size of endangered instruments mentioned in the article is not the only barrier for young players. The complexities of breath pressure, embouchure and independent control of ring-fingers are also relevant. These complexities are equally true when playing mini versions of orchestral instruments as when playing full-size ones.

The lightweight English four-hole ocarina requires simpler breath control and a more natural embouchure than any other wind instrument, including recorder; players use the first two fingers only, not ring-fingers; and each unique fingering sounds a single, accurately pitched note. The ocarina is simple enough for general class teachers to use in whole-class lessons, and musical enough for specialist teachers to introduce a full chromatic octave, advanced woodwind skills, and a broad and diverse repertoire.

My daughter, who is still less than five feet tall and has tiny hands, plays the French horn with power, skill, and confidence. She grew into this by first mastering the age-appropriate ocarina at primary level and then starting on the ‘endangered’ horn when physically and musically ready. Musical mastery at every stage has been key to her success.

There is a false attitude that first-access instruments should look like their orchestral counterparts. The ocarina could not be more different from the French horn, violin, or cello. Yet evidence shows that this simple, unsung hero can inspire early musicianship in a way that few other instruments can. Let us protect our endangered orchestral instruments. And let us also protect the less obvious ones that ‘feed’ them.

David Liggins, Kettering

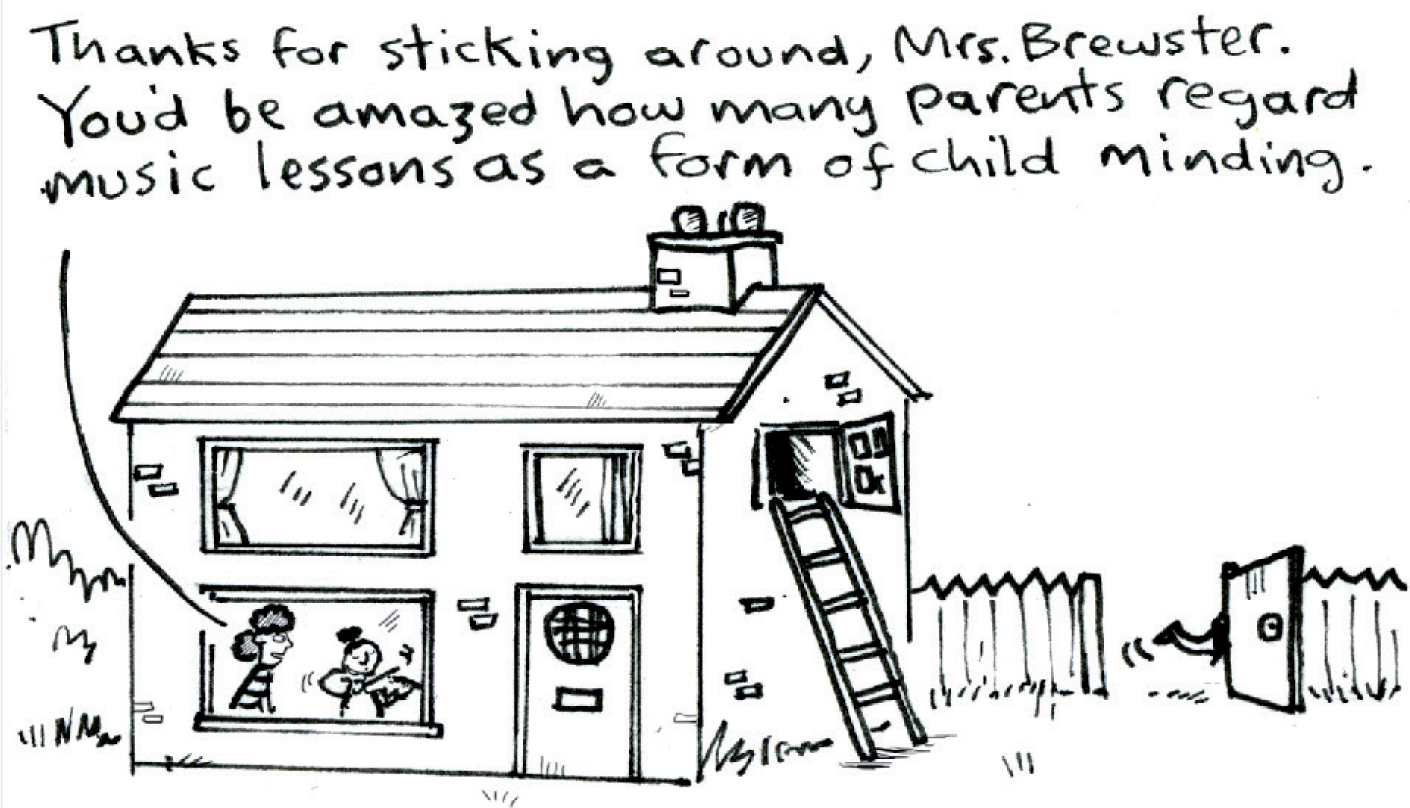

THE PERIS by Harry Venning