Composition can be great fun and inspiring for our students. But many students are left wondering which compositional process is best for showcasing their ideas – or is there a process? Much student composition seems to be trial and error.

Over the next few issues, my hope is to suggest and discuss a few useful building blocks to create a more structured approach to the way we teach composition. Assuming that students can already read notation fluently and have a basic understanding of pulse and rhythm, each month's column should offer a new compositional tool to add to their toolbox.

Focusing on one task at a time

The purpose of focusing on a single task is to allow students to grasp the importance of fundamental compositional processes in a way that is manageable, while still opening their minds to creativity and compositional development.

To begin with, we'll learn about the creative basics. Let's start with manuscript paper and a pencil. We are going to write a very short piece on one note. That's right – just one note – it could even be middle C! By doing this, many crucial aspects can be honed.

Firstly, we must think about the time signature, tempo, key signature (if necessary), and instrumentation. Whichever instrument is being written for, ensure the student is familiar with its pitch; they can google this information, which will help them become acquainted with a whole range of instruments and their capabilities.

Start by preparing the score – four bars should be sufficient to start with. I've used a treble clef, but other clefs will be required for some instruments (Fig 1).

Fig 1

Now for a discussion. Where will the note be placed in the instrument's range?

High register, middle or low? How long will it last, and how many more times will it be played? Will the notes be loud or soft, or a mixture of the two? And how might these dynamics change over time?

Some more questions: how long will the note pattern last? Will it last for a two-, four-or six-bar phrase, or just for one bar? If one bar, will this short note pattern be repeated in subsequent bars? And so on.

Imagination comes into play for this next part. Encourage students to try to imagine how the note or notes will sound. Once a student has ‘heard’ their piece, it is time to write it all down.

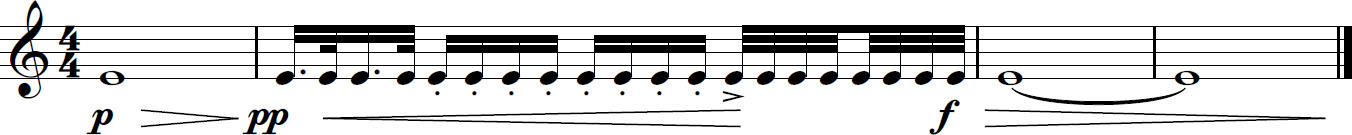

For example, I might hear a violin playing a long note that trails off into the distance before sounding again, but this time with a quick succession of notes. These are sounded softly at first, building to a fierce but powerful sonority. A much longer note concludes the passage, dying away at the end. This piece would look something like Fig 2.

Fig 2

If pupils have difficulty hearing what they want to write, aim to help them interpret their ideas. Sometimes it's just a question of playing the note pattern on the piano for them, inspiring experimentation. Ask them to feel the pulse and the rhythmic patterns.

Further explanation may be needed if their rhythmic grasp is fairly rudimentary. If this is the case, a useful exercise could be to practise writing two- or four-bar phrases, featuring varied rhythmic patterns. This way, a student can get to grips with the difficulty of adding groups of shorter notes (as in my example above) to their phrase.

Once this task has been completed, there should be a whole phrase on the page. It might consist of just a few bars, like mine, but it could be as long as eight or 12 bars. Either way, the student will have assimilated several facets of composition and is learning how to combine them and write them down, all while thinking creatively. The most beneficial part is creating the opportunity to delve into the imagination, because this is what will instigate an ‘unlocking’ process, paving the way for further musical development.