One of my long-term projects has been putting together an ethnography of voices and perceived gender, and as a result, understanding the role of technology in developing performative listening skills. This interest came out of teaching musical theatre to an incredible group of students. The group happened to include two learners in the process of transitioning gender. As a result, I became particularly interested in how gender is perceived and received in vocal terms.

What is timbre?

Timbre is one of the more problematic words we throw out in music education. Unlike the other common analytical factors we feed to our students, which have at least a basis in objectivity, the notion of timbre requires some degree of performative listening. Added to that, our delivery as educators rarely supports the development of this type of listening in our students.

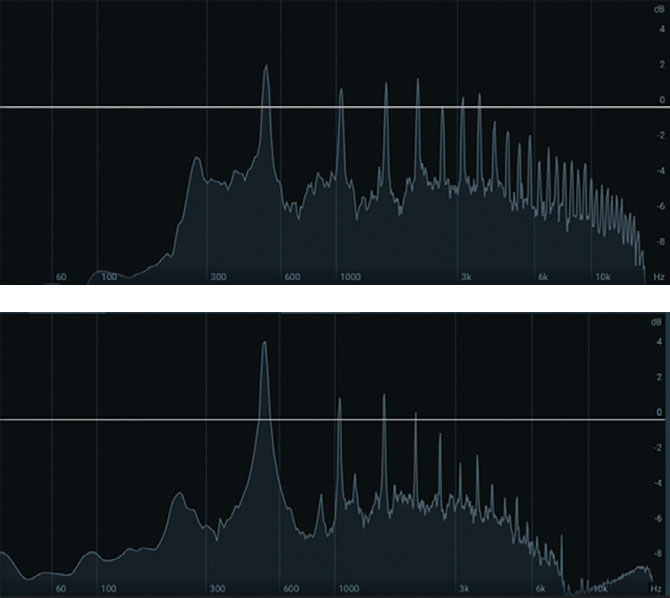

The way we understand timbre is defined by three concepts: frequency spectrum, envelope, and phase. Frequency spectrum is the relationship of the fundamental to the range of harmonics in a sound, familiar from EQ spectral analysers. Envelope is a tool more commonly found in synthesis, and maps a sound into attack, decay, sustain and release over time. Phase is the relationship of two or more different wave forms and contextualises a sound in a physical space.

What is performative listening?

We bring a series of underlying cultural assumptions to the way we interpret and understand sound. Much of this is based on the idea of timbre. The difference between the frequency spectrum of, for example, a clarinet and a violin are not as pronounced as you might imagine. The reason that we perceive these as different sounds is primarily due to the attack, or the first few milliseconds of the sound that define whether it is produced by a bow or a blow. One of my favourite class exercises is to take familiar sounds, remove the initial attack from the waveform in a DAW and ask students to work out which instrument(s) or voices produced the sound.

Spectrograph of violin (top) and clarinet (bottom) playing C4 (262 Hz)

This introduces students to the idea of listening as a performative activity – actually having to place themselves in the context of the acoustic event, rather than simply listening as an active or passive skill.

How does this relate to singers?

As schools, we are getting better at addressing cultural assumptions – both our own and those of our students. I'm pleased to say that my own students have picked me up on my use of pronouns, and some of the unconsciously gendered language I still have in my vocabulary.

The act of performative listening allows us to go further into understanding how we perceive a sound. Our brains are attuned to decoding subtleties in the human voice in a different way to our approach to listening to instruments. We make unconscious assumptions about the cultural context of a voice; age, race, gender and several other factors. These are, unsurprisingly, frequently far from accurate. I have had interesting results from playing students recordings of Joss Stone, Alison Moyet and Jeff Buckley. Even the great contralto Kathleen Ferrier has been mis-gendered by students unfamiliar with her work.

This helps students decode not only what they are hearing, but why they are interpreting the sense data in that way. This can be the starting point of a conversation on the perception of gender identity in the human voice, and the wider issue of gender roles in society. Understanding the mechanics can also help students to find their own voice by analysing the role of different aspects of their sound in creating their gender identity.

How can I help?

A number of successful apps already exist to support those transitioning in their vocal development. VoiceUp from Christella Antoni maps out spectrographic analysis in much the same way as the above. Eva (Exceptional Voice App) is another app, which also factors in the role of envelope (in this case consonant production) in producing a gender identity.

Understanding both the mechanics of how elements of vocal production are mapped on to gender and identifying those biases in my own practice has proven invaluable in supporting my students through periods of vocal change and development. I hope that is the end goal of my research. A secondary outcome is that through challenging notions of cultural assumption we can create an effective performative listening space for our students and show them the power of listening as an experience.