This is the second in a three-part series on how music technology can be used to develop musicianship, focusing on tried and tested KS3 classroom applications from the music department at Huntington School in York.

At KS3 we have designed a curriculum based on five units of work per year, with one or two of the five being technology based, depending on how the timetable shapes up. We have three classrooms in total, with one room equipped with 16 machines running Cubase and Sibelius. Students work in pairs. Classes (of 30) rotate rooms each half term to enable uniformity of access to the curriculum. We tend to use Cubase at KS3, then Cubase and Sibelius at GCSE and A Level, but any of the following uses of music technology will work on whatever sequencing package you prefer. We have been using Soundtrap and free online sequencing packages for remote and homework, but I'll come on to that in my final article.

Listening and analysing

One of my favourite things about the A Level listening paper is that students can stop and start tracks whenever they like. They are in charge. They work, within obvious constraints, at a pace that is good for them. We have brought this ownership of auditioning tracks into our KS3 music technology units of work. This ‘dwell time’ (as a curator friend of mine calls it) is proving to be a powerful tool.

In a lesson where this kind of listening task takes place (somewhere in the middle of the unit), students are given a completed version of the sequencing task they have been working on, accompanied by a series of listening questions. Questions and tasks vary in difficulty and type, from pitch identification to error fixing. Students are free to work at their own pace, auditioning, pausing, and skipping questions at will. The most commonly skipped questions become the basis for discussion and modelling in subsequent lessons.

Some questions or ‘fixing tasks’ are straightforward and analytical with right and wrong answers. That in itself is good musicianship training on many levels, but by working with a completed model, students are also able to:

- A) Refi ne their analytical skills by picking up on things that sound different to their own work, encouraging them to modify and make improvements – not because the teacher is telling them to, but because their ears are.

- B) Audition a range of devices and techniques in the improvisation and composition task examples that they can then apply in their own work.

You can find examples of ‘fixing task’ styles here.

Talking about music

Some tasks are designed to generate student conversations. Talking about what is happening in a piece of music and chatting through how to fi x errors is a key part of developing musicianship. It's a complicated thing putting sound into words. One way in which we do this in our music technology projects is through paired peer assessment. (The logistics of this simply require students to move once clockwise in the seating plan and analyse someone else's recorded work.)

In this exercise we ask students to listen and feed back on:

- What stage the work is at

- What needs to happen next (using the ‘ladder’ system as a guide – see end boxout).

After 10 minutes of discussing what they hear as a pair, students share their responses with the work's creators and then we chat as a whole class using a couple of examples to illustrate key points.

This is a ‘low stakes’ way of getting everyone thinking and talking musically. It flags up common misconceptions, and it brings specialist vocabulary to life. It is interesting how advice and feedback – from one another rather than the teacher – is received among students. In giving feedback, students are prompted to consider the next steps they want to take in their own work. By articulating this out loud, students have to refi ne both their thinking and language which, in turn, enriches their own understanding of the musical processes at work.

Also, the act of engaging in ‘music chatter’ with one another enables students to ‘rehearse’ the handling of specialist language without the pressure of speaking to the whole class. The knock-on effect is that more students speak up when you open the discussion to the whole room.

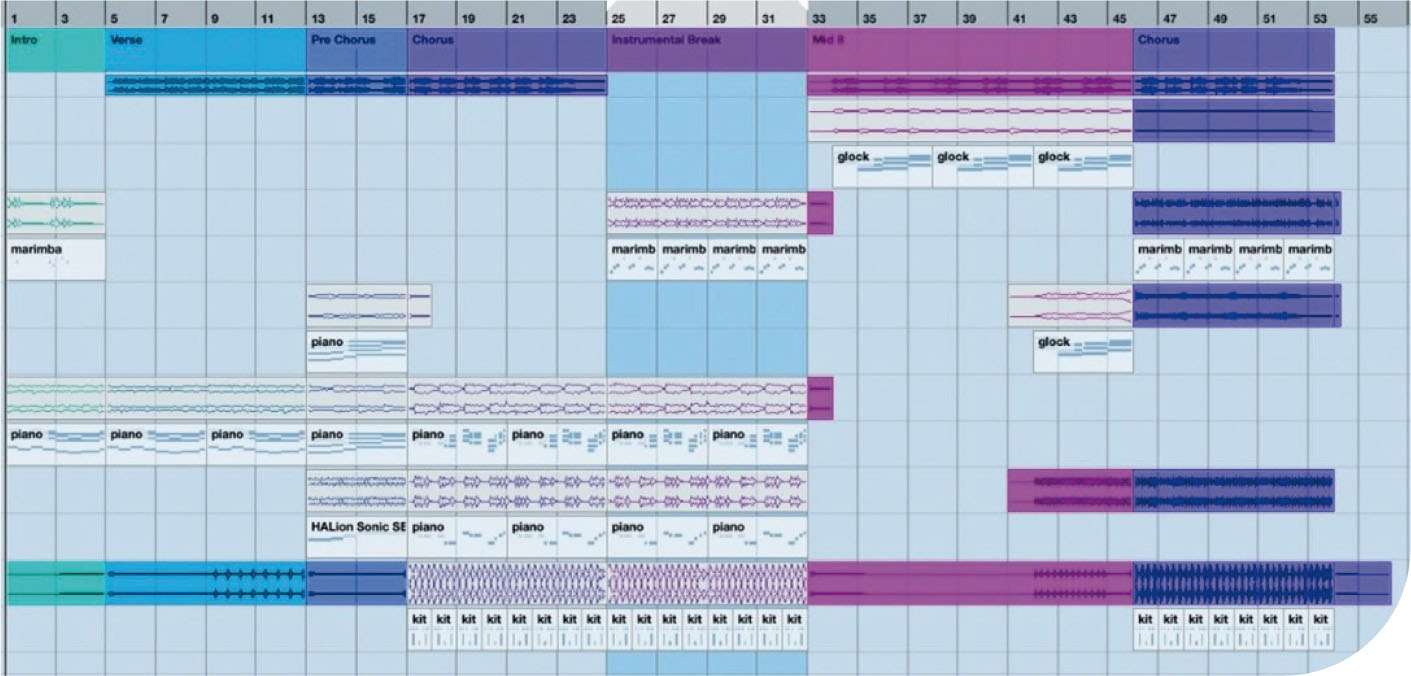

Finally, the visual rendering of musical ideas is another way in which music technology can aid the development of musical understanding and offer applications to performing, improvising, composing, and arranging. If we can ‘see’ how sections of a piece compare in terms of density of texture or duration, we can start to understand how composers balance structural variety and uniformity.

Structural frameworks and textural density made visible through music technology © HVOSTIK16/ADOBESTOCK

Structure

Students commonly struggle with structuring musical ideas. It took us long enough to realise that the reason students were finding this aspect of composition difficult was because we weren't providing them with sufficient strong, clear models. Now, all our KS3 music technology projects have some kind of structural scaffolding, like a jigsaw with pieces missing. As student experience grows, the scaffolding is gradually removed.

Using fixed structures in the early stages enables all students to produce work that ‘hangs together’. It solves the ‘128 bar intro’ problem. It solves the ‘cut and paste – is anything actually going to happen?’ problem. And of course, there's no need to stick to song structures or periodic phrasing as students gain experience, but by creating visual architectural models of the familiar, students have a picture of a stable framework as a starting point for further musical exploration.

There's so much more to say about how sequencing and recording tasks can support ‘making’ tasks that develop musicianship, but I'll continue this thread at the Music Technology in Education online conference on 18 November (www.musictechconference.co.uk/home)

You can read about the Huntington Music ladder system here.